Conflict Dynamics in the Post-FARC-EP Period and State Protection

Published: March 2020

Prepared by: Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa

This Report was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) of Canada based on approved notes from meetings with oral sources, publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This Report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee protection. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate.

Table of Contents

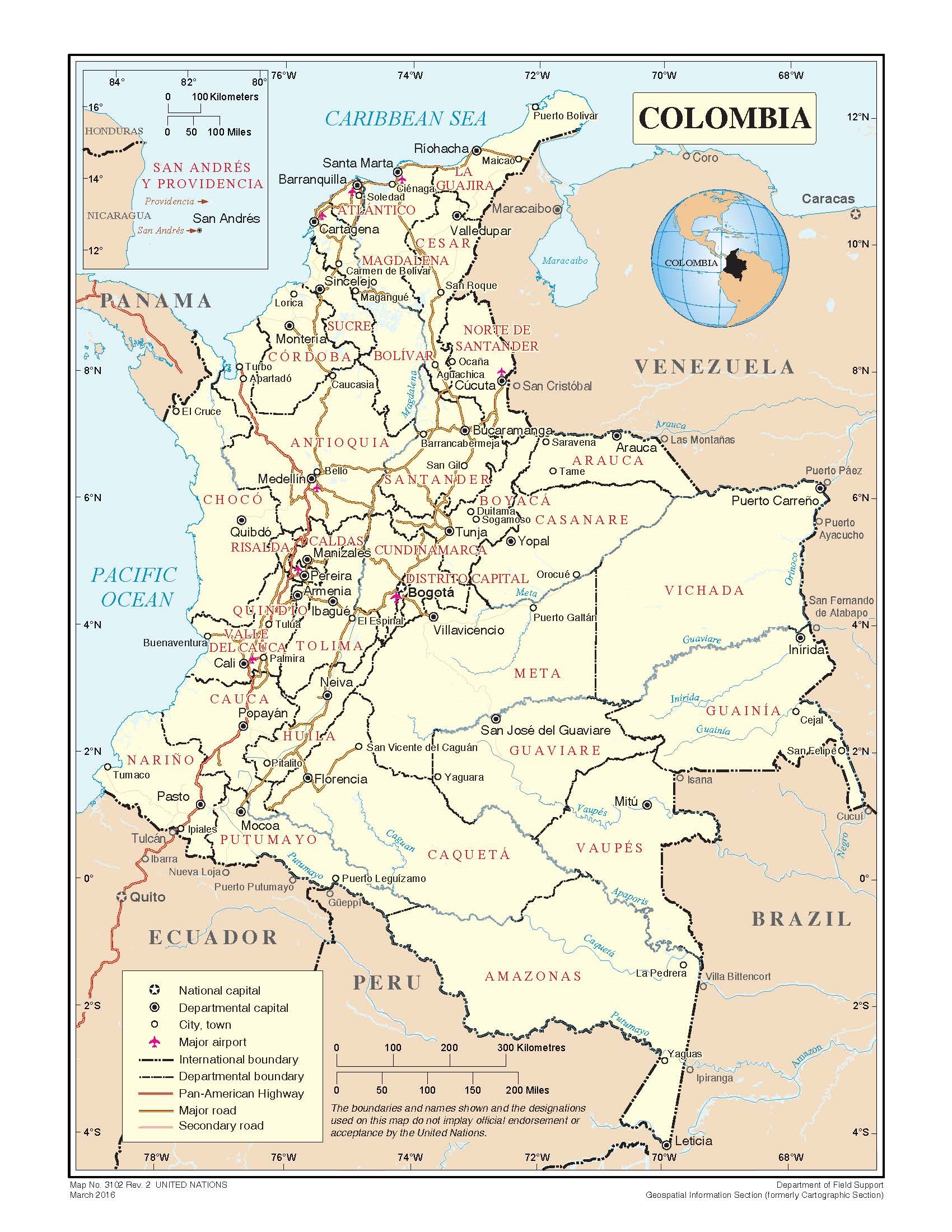

Map

Source: UN Mar. 2016

Alternate format

The image is a geographical map of Colombia.

Glossary

-

AGC

Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia) -

AUC

Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia) -

BACRIM

Bandas Criminales (Criminal Organizations) -

CERREM

Comité de Evaluación de Riesgo y Recomendación de Medidas (Committee for Risk Assessment and Recommendation of Measures) -

CLAP

Comités Locales de Abastecimiento y Producción (Local Supply and Production Committees) -

COCE

Comando Central (Central Command) [of the ELN] -

CODHES

Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement) -

COP

Colombian peso -

CTRAI

Cuerpo de Recolección y Análisis de la Información (Technical Unit for Compilation and Analysis of Information) -

ELN

Ejército de Liberación Nacional (National Liberation Army) -

EPL

Ejército Popular de Liberación (Popular Liberation Army) -

FARC

Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común (Common Alternative Revolutionary Force) -

FARC-EP

Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People's Army) -

FBL

Fuerzas Bolivarianas de Liberación (Bolivarian Liberation Forces) -

FGN

Fiscalía General de la Nación (Office of the Attorney General) -

FUDRA

Fuerza de Despliegue Rápido (Rapid Deployment Force) -

GNB

Guardia Nacional Bolivariana (Bolivarian National Guard) -

GUP

Guerrillas Unidas del Pacífico (United Guerrillas of the Pacific) -

GVP

Grupo de Valoración Preliminar (Preliminary Assessment Unit) -

ICETEX

Instituto Colombiano de Crédito Educativo y Estudios Técnicos en el Exterior (Colombian Institute of Educational Credit and Technical Studies Abroad) -

IED

Improvised Explosive Device -

IRB

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada -

JEP

Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz (Special Jurisdiction for Peace) -

LVRT

Ley de Víctimas y Restitución de Tierras (Victims and Land Restitution Law) -

NGO

Non-Governmental Organization -

OCHA

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs -

Pares

Fundación Paz y Reconciliación (Peace and Reconciliation Foundation) -

PGN

Procuraduría General de la Nación (Office of the Inspector General) -

QR Code

Quick Response Code -

RAD

Refugee Appeal Division [of the IRB] -

RPD

Refugee Protection Division [of the IRB] -

RUV

Registro Único de Víctimas (Registry of Victims) -

SAT

Sistema de Alertas Tempranas (Early Warning System) -

SEBIN

Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional (Bolivarian National Intelligence Service) -

SMLMV

Salario Mínimo Legal Mensual Vigente (Current Legal Minimum Monthly Wage) -

SNARIV

Sistema Nacional de Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas (National System for Comprehensive Victim Support and Reparation) -

TAM

Tribunal Administrativo Migratorio (Administrative Tribunal of Immigration) of Costa Rica -

UARIV

Unidad para la Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas (Victim Assistance and Comprehensive Reparation Unit) -

UBPD

Unidad de Búsqueda de Personas Dadas por Desaparecidas (Search Unit for Presumed Disappeared Persons) -

UNP

Unidad Nacional de Protección (National Protection Unit) -

UP

Unión Patriótica (Patriotic Union)

Methodology

From 4 to 8 March 2019, a joint fact-finding mission (hereafter, the mission) was carried out in Colombia by representatives of the administrative tribunals of Canada and Costa Rica that deal with matters of international protection. The Administrative Tribunal of Immigration (Tribunal Administrativo Migratorio, TAM) of Costa Rica and the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) determined the topics for the research based on the information needs of both countries. Additionally, the mission was also a Canadian capacity-building initiative to support COI research development in partner countries. The mission took place in Bogotá, Buenaventura and Cúcuta.

The mission consisted of a series of meetings with experts and officials from relevant governmental, non-governmental, academic, and research-focused organizations. Interlocutors were identified by the delegation based on their position and expertise. However, due to time constraints, the list of sources should not be considered exhaustive in terms of the scope and complexity of human rights issues in Colombia and Venezuela. Meetings with interlocutors were coordinated by the Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento, CODHES) and took place in the interlocutors' offices. All interviews were conducted in Spanish.

The purpose of the mission was to collect information on the following topics:

- The main armed groups in the period since the signing of the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People's Army (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo, FARC-EP) in 2016;

- The main profiles of people targeted by armed groups and recourse available to them;

- The situation of internal displacement; and

- Venezuelan migration to Colombia.

These areas were identified in consultation with mission participants, and IRB decision-makers from the Refugee Protection Division (RPD) and the Refugee Appeal Division (RAD). Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured approach to adapt to the expertise of the interlocutor(s) being interviewed. Interlocutors' responses to these questions varied depending on their willingness and preparedness to address them, and the length of time granted for the interview.

In accordance with the Research Directorate's methodology, which relies on publicly available information, interlocutors were advised that the information they provided would form the basis of Country-of-Origin Information (COI) reports on country conditions in Colombia and Venezuela. In this regard, interview notes were sent to interlocutors for their approval. Furthermore, interlocutors were asked to consent to being cited by a professional title or by their institution for the information they provided. They were informed that the COI reports would be publicly accessible and may be used by decision-makers adjudicating refugee claims in Canada.

This report is based on the information gathered by the IRB during the mission to Colombia, as well as publicly available documentary sources, which were included to give context to the information gathered during the mission.

This report contains information regarding the conflict dynamics in the period since the signing of the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP 2016. The first section provides brief background information about developments since the signing of the 2016 peace agreement, as well as statistics on crime and armed violence. The second section describes the main armed groups, including areas of operation, activities, and structure. The third section addresses the main profiles of people targeted by armed groups in the current context of the conflict. The fourth section provides a brief description of the internal displacement situation. The fifth section provides information about some of the protection measures available for victims of the armed conflict, as well as for the main targeted profiles identified in the third section.

This report should be read in conjunction with other IRB publications, including the following Responses to Information Requests:

-

COL106338 of July 2019: Colombia: Update to COL106087 of 1 May 2018 on the investigation of criminal complaints, including time limits, expiry of criminal proceedings, and setting aside of complaints; the Office of the Attorney General's database used to consult the status of a criminal complaint, including the definition of the different statuses (2017-July 2019)

-

COL106086 of April 2018: Colombia: The presence and activities of

Los Rastrojos, including in Buenaventura; information on their relationship with the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, AGC) [also known as Gulf Clan (Clan del Golfo) or Úsuga Clan (Clan Úsuga), and formerly known as

Los Urabeños]; state response (2017-April 2018)

-

COL106085 of April 2018: Colombia: The National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional - ELN), including number of combatants and areas of operation; activities, including ability to track victims; state response and protection available to victims (2016-April 2018)

-

COL106084 of April 2018: Colombia: The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC), including demobilization of former combatants; information on dissident groups, including number of combatants, areas of operation, activities and state response (2016-April 2018)

-

COL105773 of April 2017: Colombia: Paramilitary successor groups and criminal bands (bandas criminales, BACRIM), areas of operation and criminal activities, including the

Clan del Golfo (also known as

Urabeños or

Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia); state response, including reintregation of, and assistance to, combatants (May 2016-March 2017)

-

COL105772 of May 2017: Colombia: Requirements and procedures to submit a complaint to the police, the

Fiscalía General de la Nación, and the

Defensoría del Pueblo, including types of complaints; standardization and appearance of documents; requirements and procedures to obtain a copy of the complaint and investigative report for each organization, both from within the country and from abroad

The IRB would like to thank the Embassy of Canada in Bogotá, TAM, CODHES, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) for providing logistical support and assistance during the mission.

Overview of the Security Situation

1.1 Peace Agreement of 2016

In 2016, the government of Colombia signed a peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia - People's Army (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia - Ejército del Pueblo, FARC-EP).Footnote 1 The peace agreement included assistance to victims of the armed conflict and the creation of several institutions, such as the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz, JEP); the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence, and Non-Repetition (Comisión para el Esclarecimiento de la Verdad, la Convivencia y la No Repetición), also called the Truth Commission (Comisión de la Verdad); and the Search Unit for Presumed Disappeared Persons (Unidad de Búsqueda de Personas Dadas por Desaparecidas, UBPD).Footnote 2

The Truth Commission was created to investigate the events that took place during the armed conflict and contribute to revealing infractions or violations committed during the conflict.Footnote 3 The UBPD was created to undertake the search for disappeared persons in the context of the armed conflict and is limited to victims of forced disappearance, kidnapping, illegal recruitment, and combatants of both the armed forces and irregular armed groups.Footnote 4

In September 2017, the demobilized FARC-EP created the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force [Revolutionary Alternative Force of the Common People] (Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común, FARC) political party.Footnote 5 Some of the leaders of the FARC are currently serving as members of Congress.Footnote 6 Since the signing of the peace agreement, as of June 2019, 133 former guerrilla members of the FARC-EP have been killed and 11 have been forcibly disappeared.Footnote 7

1.2 Evolving Conflict Dynamics

The implementation of the peace agreement has been difficult due to the polarization of the complex political context in Colombia.Footnote 8 Additionally, since the signing of the peace agreement, violence and forced displacement have persisted.Footnote 9 The peace process is only partially complete as numerous [armed] actors are still present and active in the country such as other guerrilla groups, paramilitary groups, and drug trafficking organizations.Footnote 10 The Colombian government is involved in armed conflicts with the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN) and criminal organizations ([referred to by the government as]

bandas criminales, BACRIM).Footnote 11

The territories in which the FARC-EP used to operate have been taken over by other armed groups, including the ELN,Footnote 12 FARC-EP dissidents,Footnote 13 paramilitary groups, and drug trafficking organizations.Footnote 14 The presence of armed groups in these territories has led to confrontations over the control of areas that represent strategic sources of income, drug trafficking routes, and military advantage and, in the case of the dissidents of the Popular Liberation Army (Ejército Popular de Liberación, EPL), to press for a peace negotiation with the Colombian government.Footnote 15 These contested territories are experiencing renewed violence, including an increase in forced displacement, particularly in the departments of Nariño, Cauca, Valle del Cauca (particularly Buenaventura), Chocó, Arauca, and Norte de Santander, and the region of Bajo Cauca.Footnote 16

The mission heard that military operations against armed groups have affected communities living in or around conflict areas. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) notes that armed groups have responded to actions carried out by the armed forces by deploying anti-personal mines, which has reduced access to education and other social services.Footnote 17

1.3 Security Forces Operations

The Colombian government has deployed thousands of troops to combat armed groups.Footnote 18 In January 2018, the government deployed 2,000 troops to Tumaco, Nariño, as part of Operation Exodus 2018 to combat drug trafficking in the area.Footnote 19

The Office of the Ombudsperson (Defensoría del Pueblo) notes that the national government has deployed security forces in the area of Catatumbo to combat illegal armed groups. The Rapid Deployment Force (Fuerza de Despliegue Rápido, FUDRA) III and four battalions were mobilized to the city of Ocaña in October 2018 for this purpose.Footnote 20 A report produced by the Colombian Ministry of National Defense (Ministerio de Defensa Nacional) provides the following statistics on the results of the various military operations carried out by security forces:

Results of Security Operations by Colomian Armed ForcesFootnote 21

| Illegal Armed Groups (Individuals) | Jan.-Mar. 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 |

|---|

| Demobilized | 106 | 732 | 933 | 951 | 1,018 |

| Captured | 208 | 794 | 766 | 1,237 | 2,325 |

| Killed | 8 | 41 | 46 | 59 | 186 |

| Organized Criminal Organizations (Individuals) | Jan.-Mar. 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 |

|---|

| Captured | 1,129 | 4,610 | 3,113 | 3,396 | 3,073 |

| Killed | 63 | 143 | 76 | 44 | 37 |

The Peace and Reconciliation Foundation (Fundación Paz y Reconciliación, Pares) notes that the armed group made up of FARC-EP dissidents from Fronts 1 and 7 has suffered several loses and seizure of weapons during military operations. In May 2017, one of the treasurers was killed during a joint operation between the National Police and the army; in September 2017, the army killed Alfonso Lizcano Gualdrón, one of the leaders of Front 1; and in March 2018, nine members were killed in a military operation.Footnote 22

1.4 Criminality and Armed Violence Trends

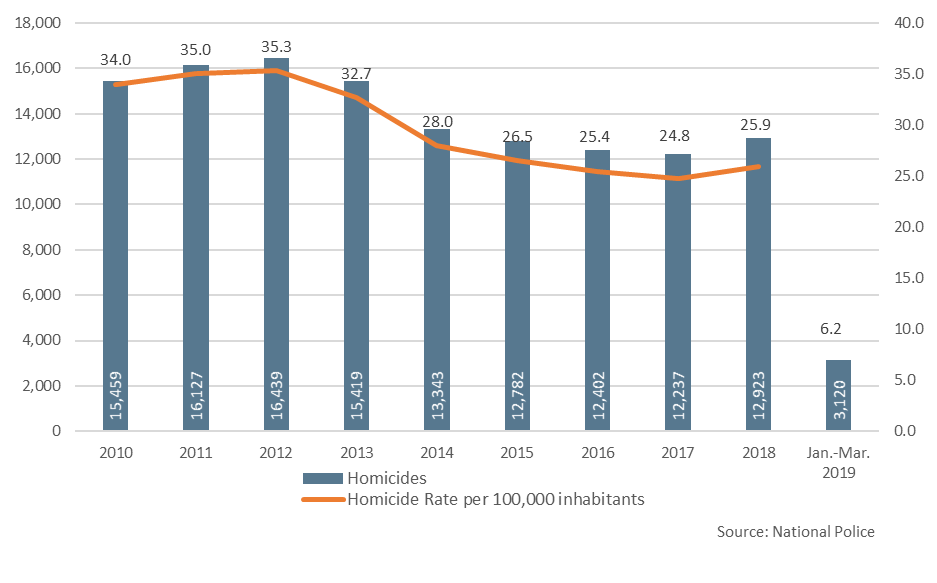

Although rates of homicides and forced displacement have declined since 2012 or since the agreements with the FARC,Footnote 23 crimes such as extortion and drug trafficking continue.Footnote 24 The incursion of new armed actors in the armed conflict and the expansion of those that were already present are creating new conflict dynamics,Footnote 25 particularly the increasing rates of homicides in 2018 of social leaders and aggressions against ex-combatants.Footnote 26

Number of Homicides and Homicide RateFootnote 27

Alternate format

The image is a bar chart indicating the number of homicides and homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants from 2010 to January-March 2019. The data source is the National Police.

- 2010: 15,459 homicides and a homicide rate of 34 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- 2011: 16,127 homicides and a homicide rate of 35 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- 2012: 16,439 homicides and a homicide rate of 35.3 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- 2013: 15,419 homicides and a homicide rate of 32.7 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- 2014: 13,343 homicides and a homicide rate of 28 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- 2015: 12,782 homicides and a homicide rate of 26.5 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- 2016: 12,402 homicides and a homicide rate of 25.4 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- 2017: 12,237 homicides and a homicide rate of 25.9 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- 2018: 12,923 homicides and a homicide rate of 28 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- January-March 2019: 3,120 homicides and a homicide rate of 6.2 per 100,000 inhabitants.

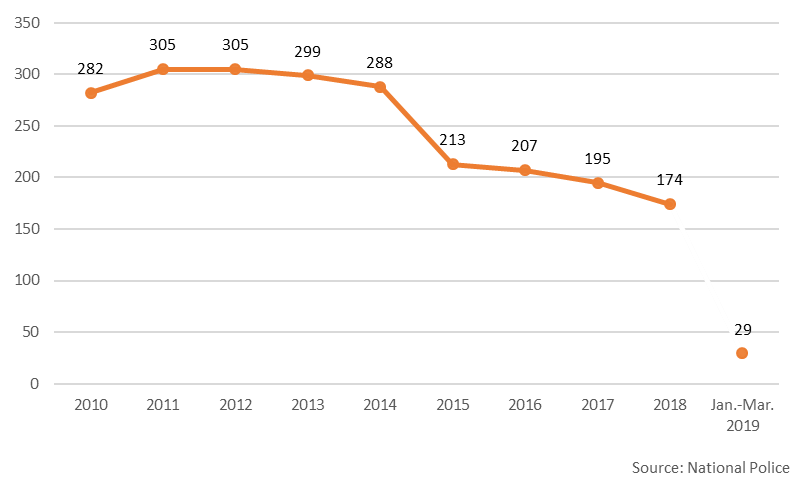

Pares notes that rates of forced disappearances and kidnappings have decreased over the years. While for 2002 there were 16,026 disappearances reported, numbers progressively dropped to 137 in 2015, 74 in 2016, 72 in 2017, and 39 in 2018.Footnote 28 Similarly, at the end of the 1990s, over 3,000 kidnappings were reported, while in 2017 and in the first half of 2018 these numbers dropped to 193 and 92 cases, respectively.Footnote 29 The Ministry of National Defense provides similar numbers:

Alternate format

The image is a broken line chart indicating the number of kidnappings from 2010 to January-March 2019. The data source is the National Police.

- 2010: 282 kidnappings.

- 2011: 305 kidnappings.

- 2012: 305 kidnappings.

- 2013: 299 kidnappings.

- 2014: 288 kidnappings.

- 2015: 213 kidnappings.

- 2016: 207 kidnappings.

- 2017: 195 kidnappings.

- 2018: 174 kidnappings.

- January-March 2019: 29 kidnappings.

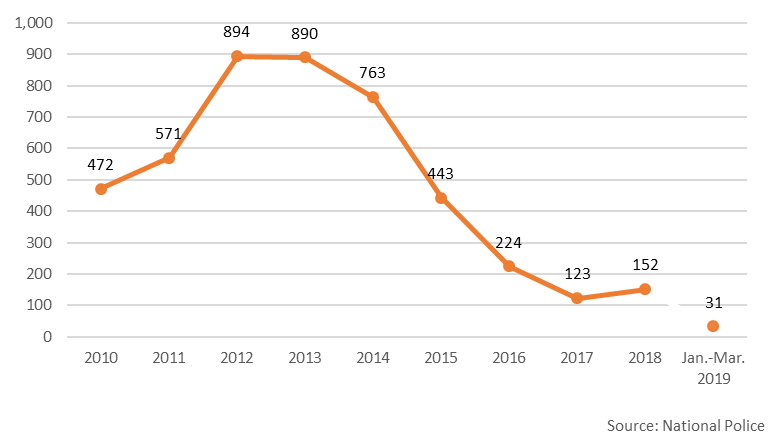

Regarding [translation] "terrorist acts"Footnote 31 and "subversive acts"Footnote 32 committed by armed groups, the National Police provides the following statistics:

"Terrorist Acts" Reported by the National PoliceFootnote 33

Alternate format

The image is a broken line chart indicating the number of "terrorist acts" reported by the National Police from 2010 to January-March 2019. The data source is the National Police.

- 2010: 472 terrorist acts.

- 2011: 571 terrorist acts.

- 2012: 894 terrorist acts.

- 2013: 890 terrorist acts.

- 2014: 763 terrorist acts.

- 2015: 443 terrorist acts.

- 2016: 224 terrorist acts.

- 2017: 123 terrorist acts.

- 2018: 152 terrorist acts.

- January-March 2019: 31 terrorist acts.

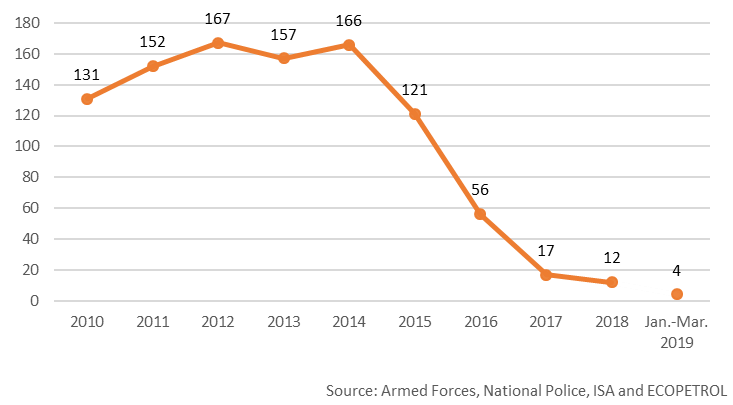

"Subversive Acts" Reported by the National PoliceFootnote 34

Alternate format

The image is a broken line chart indicating the number of "subversive acts" reported by the National Police from 2010 to January-March 2019. The data sources are the Armed Forces, the National Police, ISA, and ECOPETROL.

- 2010: 131 subversive acts.

- 2011: 152 subversive acts.

- 2012: 167 subversive acts.

- 2013: 157 subversive acts.

- 2014: 166 subversive acts.

- 2015: 121 subversive acts.

- 2016: 56 subversive acts.

- 2017: 17 subversive acts.

- 2018: 12 subversive acts.

- January-March 2019: 4 subversive acts.

CODHES provides the following statistics on warlike actions:Footnote 35

Warlike Actions (acciones bélicas)Footnote 36 - 1 January 2019 to 28 February 2019

| Department | Number of Events | Warlike Actions | Warlike Actions that Led to Violations of International Humanitarian LawFootnote 37 | Violations of International Humanitarian Law |

|---|

|

Total |

111 |

45 |

25 |

41 |

| Nariño | 19 | 14 | 3 | 2 |

| Cauca | 17 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| Antioquia | 14 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Norte de Santander | 14 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Valle del Cauca | 9 | 1 | - | 8 |

| Chocó | 8 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Arauca | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Putumayo | 5 | 1 | 4 | - |

| Magdalena | 4 | 2 | - | 2 |

| La Guajira | 2 | 1 | - | 1 |

| Tolima | 2 | 1 | - | 1 |

| Atlántico | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Bogotá | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Bolívar | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Caldas1 | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Caquetá | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| César | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Córdoba | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Cundinamarca | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Guaviare | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Huila | 1 | 1 | - | - |

Warlike Actions - 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2018

| Department | Number of Events | Warlike Actions | Warlike Actions that Led to Violations of International Humanitarian Law | Violations of International Humanitarian Law |

|---|

|

Total |

1161 |

579 |

139 |

443 |

| Antioquia | 251 | 126 | 48 | 77 |

| Nariño | 137 | 76 | 10 | 51 |

| Cauca | 132 | 62 | 14 | 56 |

| Norte de Santander | 88 | 36 | 15 | 37 |

| Chocó | 63 | 24 | 15 | 24 |

| Tolima | 45 | 11 | 0 | 34 |

| Bolívar | 44 | 25 | 7 | 13 |

| Córdoba | 42 | 13 | 6 | 23 |

| Meta | 38 | 25 | 1 | 12 |

| Valle del Cauca | 35 | 17 | 3 | 15 |

| Arauca | 33 | 21 | 3 | 9 |

| Atlántico | 31 | 18 | 1 | 12 |

| Caquetá | 31 | 20 | 1 | 10 |

| Huila | 30 | 19 | 0 | 11 |

| César | 25 | 4 | 5 | 16 |

| Putumayo | 25 | 17 | 1 | 7 |

| Sucre | 24 | 10 | 5 | 9 |

| Guaviare | 16 | 13 | 1 | 2 |

| Bogotá | 13 | 8 | 1 | 4 |

| Magdalena | 11 | 7 | 0 | 4 |

| Casanare | 10 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Risaralda | 7 | 7 | 0 | - |

| Cundinamarca | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| La Guajira | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Amazonas | 4 | 4 | 0 | - |

| Boyacá | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Caldas | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Vichada | 3 | 3 | 0 | - |

| Guainía | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Santander | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| San Andrés | 1 | 1 | 0 | - |

| Vaupés | 1 | - | 0 | 1 |

2. Armed Groups

A report produced by several government agencies, including the Office of the Ombudsperson and the Office of the Inspector General (Procuraduría General de la Nación, PGN), on the monitoring and oversight of the implementation of Law 1448 of 2011, the Victims and Land Restitution Law (Ley de Víctimas y Restitución de Tierras, LVRT), between 2014 and 2018, indicates that territorial control by armed groups is being reconfigured in different parts of the country.Footnote 38 In some areas, this dynamic of territory disputes between armed groups has included threats and attacks against human rights advocates and leaders of social and political organizations.Footnote 39

The OCHA indicates that attacks against the population in 2018 were committed by the following groups:

- unknown actors (59 percent);

- the EPL (11 percent);

- the ELN (10 percent);

- organized armed groups, including the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, AGC) and the Gulf Clan (Clan del Golfo) (9 percent);

- other armed groups (7 percent);

- dissidents of the FARC-EP (2 percent);

- and clashes among other armed actors (3 percent).

These attacks included threats (725 cases), murder of a [translation] "protected person" (672), kidnappings (111), massacres (27), and other categories including forced recruitment, forced disappearance, torture, use of civilians as shields during combat, hostage taking, sexual violence, and the killing of civilians during armed confrontations (530).Footnote 40

A document prepared by the Research Directorate based on information provided by CODHES on the presence of armed groups as reported in all 1,122 municipalities in Colombia is attached to this report. The attached document provides information on the 10 most significant armed groups by department and departmental capital. For information on presence of armed groups in a particular municipality as of December 2018, please contact the Research Directorate.

Presence of Armed Groups by Department and Departmental Capital, December 2018

Presence of Armed Groups by Department and Departmental Capital, December 2018

Note: This document was prepared by the Research Directorate based on the information of the presence of armed groups in all 1,122 municipalities of Colombia, in addition to Bogotá, D.C., provided by the Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES). For information on the presence of an armed group in particular municipalities as reported by CODHES as of December 2018, please contact the Research Directorate.

| Department | Municipalities | Departmental Capital | Armed group | Number of municipalites that reported on its presence | Reported presence in the capital of the department |

|---|

| Amazonas | 11 | Leticia | FIAC | 3 | Yes |

| | | FD | 3 | No |

| | | FD Front 1 | 2 | Yes |

| | | LV | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Caqueteños | 1 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 1 | No

|

| Antioquia | 125 | Medellín | AGC | 125 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 36 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 21 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 19 | No |

| | | PH | 18 | Yes |

| | |

Los Pachelly | 13 | Yes |

| | | FD | 9 | No |

| | | OE | 8 | Yes |

| | |

Caparrapos | 8 | No |

| | | FD Front 36 | 7 | No |

| Arauca | 7 | Arauca | AGC | 7 | Yes |

| | | A. Casanare | 7 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 7 | Yes |

| | | FIAC | 4 | Yes |

| | | FD - Front 10 | 4 | No |

| | | FD | 3 | Yes |

| | | PH | 3 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 3 | No |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 1 | No |

| Atlántico | 23 | Barranquilla |

Rastrojos C. | 23 | Yes |

| | | AGC | 8 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 6 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 3 | Yes |

| | | PH | 18 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 3 | Yes |

| | | Gangs | 2 | Yes |

| | | OE | 1 | Yes |

| | | PH | 1 | No |

| | |

Los Pachenca | 1 | Yes |

| Bogotá, D.C. | 1 | Bogotá, D.C. | AGC | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 1 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Los Paisas | 1 | Yes |

| | | AUC | 1 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 1 | Yes |

| Bolívar | 46 | Cartagena | AGC | 45 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 14 | No |

| | | GASI | 11 | Yes |

| | | CG

| 4 | No |

| | | PH | 3 | No |

| | |

Rastrojos | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Los de la 18 | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Los del Hoyo | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Los Pachenca | 1 | Yes |

| Boyacá | 123 | Tunja | AGC | 7 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 5 | No |

| | |

Rastrojos | 3 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 1 | No |

| | | FIAC | 1 | No |

| | | PH | 1 | No |

| Caldas | 27 | Manizales | GASI | 3 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 1 | Yes |

| | | AGC | 1 | No |

| | | BHG | 1 | No |

| | | ELN | 1 | No |

| Caquetá | 16 | Florencia | AGC | 13 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 13 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 5 | Yes |

| | | FD | 5 | Yes |

| | | FD - Front 14 | 4 | No |

| | | FD - Front 62 | 3 | Yes |

| | | PH | 3 | No |

| | | FD - Front 1 | 2 | Yes |

| | | FD - Front 7 | 2 | No |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 1 | No |

| Casanare | 19 | Yopal | BHG | 6 | No |

| | | ELN | 5 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 2 | No |

| | | AGC | 1 | No |

| | | FD | 1 | No |

| Cauca | 42 | Popayán |

Águilas Negras | 42 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 39 | Yes |

| | | AGC | 34 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 28 | Yes |

| | | FD | 11 | No |

| | |

Rastrojos | 10 | Yes |

| | | PH | 8 | No |

| | | AUC | 5 | No |

| | | FD - Juvenal | 5 | No |

| | |

FD - Los Pija | 4 | No |

| Cesar | 25 | Valledupar | AGC | 25 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 16 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 11 | Yes |

| | | ELP - LP | 8 | No |

| | | FIAC | 7 | No |

| | | FD | 7 | No |

| | | GASI | 3 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 2 | Yes |

| | | PH | 1 | No |

| | | FD - Front 33 | 1 | No |

| Chocó | 31 | Quibdó | AGC | 31 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 26 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 9 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 5 | Yes |

| | | CG | 4 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 2 | No |

| | | PH | 2 | No |

| | | FD | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Renacer | 1 | No |

| | | Gangs | 1 | No |

| Córdoba | 30 | Montería | AGC | 29 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 10 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 7 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 4 | No |

| | | FD | 3 | No |

| | | PH | 3 | No |

| | | FD - Front 36 | 2 | No |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 1 | Yes |

| | |

Caparrapos | 1 | No |

| | | CG | 1 | No |

| Cundinamarca | 125 | Bogotá, D.C. | AGC | 13 | See presence in the Bogotá, D.C. section |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 6 | |

| | | ELN | 4 | |

| | | GASI | 2 | |

| | | PH | 1 | |

| Guainía | 9 | Puerto Inírida | FIAC | 6 | Yes |

| | | FD - FAM | 1 | Yes |

| | | AGC | 1 | No |

| | | ELN | 1 | No |

| Guaviare | 4 | San José del Guaviare | AGC | 4 | Yes |

| | | LV | 4 | Yes |

| | | FIAC | 4 | Yes |

| | |

Los Rudos | 4 | Yes |

| | | BG | 4 | Yes |

| | | FD | 4 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 4 | Yes |

| | |

Bloque Meta

| 2 | Yes |

| | | FD - Front 1 | 2 | No |

| | | FD - Front 7 | 1 | Yes |

| La Guajira | 15 | Rioacha | AGC | 15 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 8 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 8 | Yes |

| | | FIAC | 7 | No |

| | |

LA Mano Negra | 4 | No |

| | |

Rastrojos | 3 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 3 | Yes |

| | |

Los Pachenca | 2 | Yes |

| | | AUC | 1 | No |

| Huila | 37 | Neiva | AGC | 18 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 18 | Yes |

| | | FD | 6 | No |

| | | FD - Front 17 | 6 | No |

| | | GASI | 5 | No |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 4 | Yes |

| | | PH | 2 | No |

| | | AUC | 1 | No |

| Magdalena | 30 | Santa Marta | AGC | 30 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 8 | No |

| | | GASI | 4 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 2 | Yes |

| | | FD | 1 | Yes |

| | | Gangs | 1 | No |

| | | ELN | 1 | No |

| | | EPL - LP | 1 | No |

| Meta | 29 | Villavicencio | LV | 29 | Yes |

| | | FIAC | 29 | Yes |

| | |

Bloque Meta | 21 | Yes |

| | | AGC | 20 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 15 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 12 | Yes |

| | | PE | 10 | Yes |

| | | FD | 7 | No |

| | | FD - Front 1 | 5 | No |

| | | PH | 3 | Yes |

| Nariño | 64 | Pasto | AGC | 64 | Yes |

| | |

Los Paisas | 64 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 34 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 23 | Yes |

| | | FD | 16 | No |

| | |

Rastrojos | 13 | No |

| | | PH | 10 | No |

| | | GO | 9 | No |

| | | FD - FOS | 7 | No |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 6

| No |

| Norte de Santander | 40 | Cúcuta | AGC | 40 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 24 | Yes |

| | | EPL - LP | 11 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 10 | Yes |

| | | FIAC | 9 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 8 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 4 | No |

| | | FD - Front 33 | 4 | No |

| | | PH | 3 | Yes |

| | | FD | 3 | No |

| Putumayo | 13 | Mocoa | AGC | 9 | No |

| | | ELN | 9 | No |

| | | GASI | 8 | Yes |

| | |

La Constru | 7 | No |

| | |

Rastrojos | 5 | No |

| | | FD | 5 | No |

| | | FD - Front 48 | 4 | No |

| | | PH | 3 | No |

| | | FD - Front 1 | 2 | No |

| | | Gangs | 1 | No |

| Quindío | 12 | Armenia |

Rastrojos | 12 | Yes |

| | | AGC | 6 | Yes |

| | |

Cordillera | 2 | No |

| | | GASI | 1 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 1 | No |

| Risaralda | 14 | Pereira | AGC | 11 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 5 | Yes |

| | |

Cordillera | 4 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 2 | Yes |

| | | PH | 2 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 2 | No |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 1 | Yes |

| | | BHG | 1 | No |

| | | EPL - LP | 1 | No |

| San Andrés y Providencia | 2 | | AGC | 2 | |

| | |

Rastrojos | 1 | |

| | | GASI | 1 | |

| | |

La Constru | 1 | |

| Santander | 87 | Bucaramanga | AGC | 87 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 12 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 8 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 2 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 1 | No |

| | |

Botalones | 1 | No |

| Sucre | 26 | Sincelejo | AGC | 26 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 9 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 5 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 3 | Yes |

| | | OE | 1 | No |

| | | FD | 1 | No |

| Tolima | 47 | Ibagué | PH | 14 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 13 | Yes |

| | | AGC | 12 | Yes |

| | | GASI | 12 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 10 | No |

| | | HV | 8 | No |

| | | AUC | 2 | No |

| | | FD | 2 | No |

| | |

Renacer | 1 | No |

| | | Comando Niche | 1 | No |

| Valle del Cauca | 42 | Cali | AGC | 42 | Yes |

| | |

Rastrojos | 42 | Yes |

| | |

Buenaventureños | 42 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 18 | Yes |

| | | HV | 16 | No |

| | | GASI | 11 | Yes |

| | |

Machos | 5 | No |

| | | FD | 3 | Yes |

| | | PH | 3 | Yes |

| | |

Águilas Negras | 2 | Yes |

| Vaupés | 6 | Mitú | FIAC | 3 | Yes |

| | | FD | 2 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 2 | Yes |

| | | AGC | 1 | Yes |

| | | PH | 1 | No |

| Vichada | 4 | Puerto Carreño |

Bloque Meta | 3 | Yes |

| | | LV | 3 | Yes |

| | | AGC | 2 | Yes |

| | | FIAC | 2 | Yes |

| | | ELN | 2 | Yes |

| | | FD | 1 | No |

| | | FD - FAM | 1 | No |

Source:Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES), provided to the Research Directorate, 12 July 2019.

Abbreviations

A. Casanare:

Autodefensas del Casanare

AGC:

Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia

AUC:

Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia

BG:

Bloque Ganadero

BHG:

Bloque Héroes de Guática

CG:

Clan del Golfo

ELN:

Ejército de Liberación Nacional

EPL - LP:

Ejército Popular de Liberación - Los Pelusos

FAM:

Frente Acacio Medina (Dissidence of the FARC-EP)

FD: FARC-EP dissidents

FIAC:

Fuerzas Armadas Irregulares de Colombia

FOS:

Frente Óliver Sinisterra (Dissidence of the FARC-EP)

GASI:

Grupos armados sin identificar (Unidentified armed groups)

GO:

Gente el Orden

HV:

Héroes del Valle

LV:

Libertadores del Vichada

OE:

Oficina de Envigado

PE:

Puntilleros del ERPAC (Ejército Revolucionario Popular Antisubersivo de Colombia)

PH:

Paramilitary heirs

Rastrojos C.:

Rastrojos Costeños

Citation: Research Directorate. July 2019. Presence of Armed Groups by Department and Departmental Capital, December 2018. A compilation of data provided to the Research Directorate by

Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES), 12 July 2019.

2.1 ELN

The ELN, which emerged in 1964 and was inspired by the Cuban revolution,Footnote 41 is one of the "two main guerrilla armies with left-wing political ideologies operating in Colombia."Footnote 42 The ELN has been weakened militarily in recent years, with the number of combatants dropping from approximately 5,000 in the mid-1990s (in addition to "at least" 15,000 sympathizers that included students, union activists and political supporters),Footnote 43 to current estimates of 1,700Footnote 44 or 2,500.Footnote 45

The ELN is divided into Fronts (Frentes) and also has urban militias in some major cities and in many small towns.Footnote 46 The ELN has six Fronts, six companies, and two urban Fronts which have [translation] "at least" 639 combatants.Footnote 47 The ELN's National Directorate (Dirección Nacional) consists of 23 members, and the Central Command (Comando Central, COCE) is made up of five commanders who are in charge of a different area: military affairs, political affairs, international affairs, finance, and communications (between the COCE and the ELN's Fronts).Footnote 48 The members of the COCE are Nicolás Rodríguez Bautista, also known as "'Gabino'," [who is the leader of the ELNFootnote 49]; Gustavo Aníbal Giraldo, also known as "'Pablito'"; Eliécer Herlinton [Herlinto] Chamorro, also known as "'Antonio García'"; Israel Ramírez, also known as "'Pablo Beltrán'"; and Rafael Sierra Granados, also known as "'Ramiro Vargas'."Footnote 50

The ELN is considered a [translation] "federative guerilla" organization with a horizontal chain of command, and it is the most experienced among current guerrilla groups.Footnote 51 The ELN is also reported to have a diffuse chain of command.Footnote 52

The ELN operates in 99 municipalitiesFootnote 53 in nine departments, particularly in the northeast of Colombia.Footnote 54 It has a strong presence in the city of Cúcuta, being superior to Los Rastrojos, Los Pelusos and the Front 33 of the dissidents of the FARC-EP.Footnote 55 InSight Crime notes that the ELN is also present in the departments of Arauca and Norte de Santander, as well as Apure in Venezuela, which represents a strategic area to control drug trafficking routes and flows between the two countries. With the demobilization of the FARC-EP, the ELN increased its presence in the border area in Venezuela, particularly through the Fronts Domingo Laín Sáenz, one of the most powerful structures of the ELN, and Carlos Germán Velasco Villamizar, which is based in Cúcuta and extends its operations to surrounding areas.Footnote 56

Activities of the ELN include kidnapping, extortion, attacks on economic infrastructure, drug trafficking-related activities,Footnote 57 [translation] "selective homicides," threats, looting, armed strikes, recruitment of children and adolescents, deployment of anti-personnel mines, and deployment of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) next to protected areas, military and police stations, and oil infrastructure.Footnote 58

The Office of the Ombudsperson identified the following targeted profiles by the ELN in the department of Arauca: social leaders, directors of communal associations and victims' organizations, human rights advocates, public servants, drug users, sex workers, homeless people, Venezuelan citizens [crossing into Colombia], women who are perceived to have relationships with members of the armed forces, and children and young people for the purposes of forced recruitment.Footnote 59

In the area of Catatumbo, Norte de Santander, the ELN has presence with Front Nororiental, and Fronts Camilo Torres Restrepo, Carlos Armando Cacua Guerrero, Compañero Héctor, and the Companies Comandante Diego, Héroes del Catatumbo, and other clusters called [translation] "'public order' commissions" that operate along the border with Venezuela.Footnote 60

In February 2017, the Colombian government launched a peace process with the ELN in Quito, Ecuador.Footnote 61 However, in April 2018 the Ecuadorian government withdrew its support claiming security concerns, with the President of Ecuador indicating that Ecuador will not host peace negotiations as long as the ELN continues to engage in [translation] "terrorist acts."Footnote 62 The negotiations were moved to Cuba,Footnote 63 but on 17 January 2019, the ELN detonated a car bomb against a police training centre in Bogotá, killing 20 police officers.Footnote 64 As a result, President Duque suspended negotiations with the ELN, reactivated the arrest warrants against the delegation participating in the negotiations, and demanded Cuba extradite them to Colombia.Footnote 65 The Colombian government and the ELN had previously attempted peace negotiations in 2002 and 2004-2005.Footnote 66

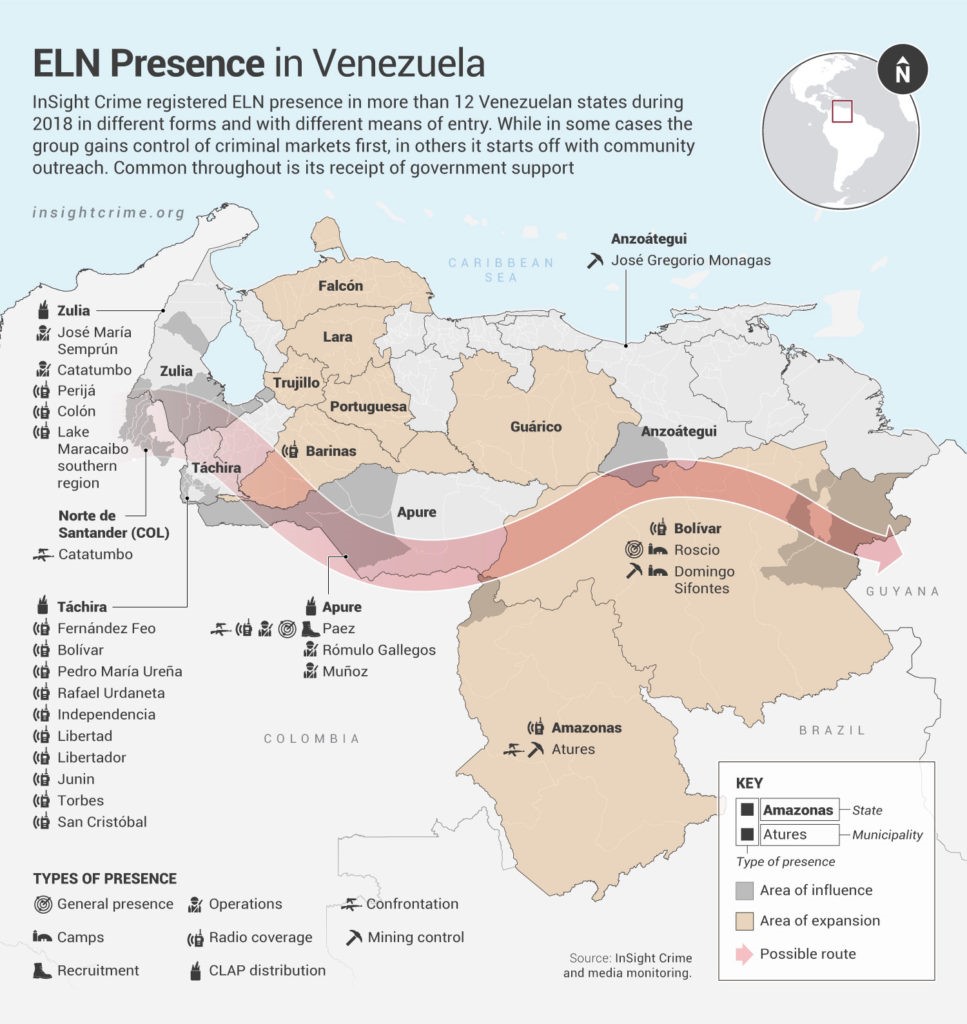

2.1.1 The ELN in Venezuela

Interlocutors stated that the ELN is increasing its presence and operations capacity in Venezuela. A map produced by InSight Crime indicates the Venezuelan states in which this group is present:Footnote 67

Alternate format

The image is a map of the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional —ELN) presence in Venezuela, prepared by Insight Crime and published on March 11, 2019. A short text at the top of the map reads as follows:

"Insight Crime registered ELN presence in more than 12 Venezuelan states during 2018 in different forms and with different means of entry. While in some cases the group gains control of criminal markets first, in others it starts off with community outreach. Common throughout is its receipt of government support."

The map indicates the parts of Venezuela where the presence of the ELN has been reported. The areas where the ELN's presence has been recorded are identified either as "areas of influence" or "areas of expansion" of the ELN. The areas of influence of the ELN are the following:

- Some parts of the state of Zulia, especially in the South.

- Some parts of the state of Táchira, especially in the West.

- Some parts of the state of Apure, especially in the West.

- Some parts of the state of Anzoátegui, especially in the South-West.

The areas of expansion of the ELN are the following:

- The state of Falcón.

- The state of Lara.

- The state of Trujillo.

- The state of Portuguesa.

- The state of Barinas.

- The state of Guárico.

- The state of Bolívar.

- The state of Amazonas.

The map further categorizes the types of presence as follows: "general presence", "camps", "recruitment", "operations", "radio coverage", "CLAP distribution", "confrontation", and "mining control".

The areas where the type of presence is identified as "general presence" are the following:

- The municipality of Paez, in the state of Apure.

- The municipality of Roscio, in the state of Bolívar.

The areas where the presence of ELN camps has been reported are the following:

- The municipalities of Roscio and Domingo Sifontes, in the state of Bolívar.

The area where recruitment by the ELN has been reported is the following:

- The municipality of Paez, in the state of Apure.

The areas where operations of the ELN have been reported are the following:

- The municipalities of José María Semprún and Catatumbo, in the state of Zulia.

- The municipalities of Paez, Rómulo Gallegos, and Muñoz, in the state of Apure.

The areas where radio coverage by the ELN have been reported are the following:

- The municipalities of Perijá, Colón, and Lake Maracaibo southern region, in the state of Zulia.

- The municipalities of Fernández Feo, Bolívar, Pedro María Ureña, Rafael Urdaneta, Independencia, Libertad, Libertador, Junin, Torbes, San Cristóbal, in the state of Táchira.

- The state of Barinas.

- The municipality of Paez, in the state of Apure.

- The state of Bolívar.

- The state of Amazonas.

The areas where CLAP distribution by the ELN have been reported are the following:

- The state of Zulia.

- The state of Táchira.

- The state of Apure.

The areas where confrontation involving the ELN has been reported are the following:

- The municipality of Paez, in the state of Apure.

- The municipality of Atures, in the state of Amazonas.

- The municipality of Catatumbo, in the department of Norte de Santander in Colombia (west of the Venezuelan state of Táchira).

The areas where mining control by the ELN has been reported are the following:

- The municipality of José Gregorio Monagas in the state of Anzoátegui.

- The municipality of Domingo Sifontes in the state of Bolívar.

- The municipality of Atures, in the state of Amazonas.

The map further includes an arrow corresponding to a "possible route" for the ELN. The arrow runs across Venezuela, from West towards East of the country, passing through the states of Zulia, Táchira, south-west of Barinas, Apure, and Bolívar (while crossing slightly in the south-west of Anzoátegui), in that order.

Activities in which the ELN has reportedly engaged in Venezuela include kidnapping, extortion, cross-border drug trafficking, and gasoline smuggling.Footnote 68 The ELN has also been involved in the distribution of food boxes known as Local Supply and Production Committees (Comités Locales de Abastecimiento y Producción, CLAP),Footnote 69 which is a social program of the Venezuelan government.Footnote 70 According to InSight Crime, the ELN has also worked with the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia Nacional, SEBIN), the Bolivarian National Guard (Guardia Nacional Bolivariana, GNB), and the Bolivarian Liberation Forces (Fuerzas Bolivarianas de Liberación, FBL) [also called the Patriotic Forces of National Liberation --

Fuerzas Patrióticas de Liberación Nacional, FPLN], although it has engaged in clashes with the FBL for territorial control in the state of Apure. The ELN also uses Venezuelan territory as a hideout, including for its leader.Footnote 71

2.2 Dissidents of the FARC-EP

According to lists provided by the FARC-EP in August 2017 in the context of the peace negotiations, the number of members of the FARC-EP was 15,001. However, according to the Colombian government's Office of the High Commissioner for Peace (Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz), the list included duplicate or erroneous entries, and formally recognized a total of 13,049 as members of the FARC-EP, including demobilized guerrilla fighters, militia operatives, foreign members, and members serving prison sentences.Footnote 72

FARC-EP dissidents started to operate during the peace negotiations.Footnote 73 On 10 June 2016, the dissidents of Front 1 refused to demobilize, stating that the State only seeks [translation] "the disarmament and demobilization of guerrillas, and is not trying solve the country's social and economic problems."Footnote 74 A BBC article, however, reports that the interest behind the refusal to demobilize is to keep the sources of income of illicit activities such as coca cultivation and illegal mining.Footnote 75 For example, it is reported that approximately 300 members of Fronts 1 and 7 of the FARC-EP abandoned peace negotiations and continued activities in the departments of Guaviare, Guainía and Vaupés.Footnote 76 About half of these 300 members joined other groups such as Gente de Orden, United Guerrillas of the Pacific (Guerrillas Unidas del Pacífico, GUP), and the Óliver Sinisterra Front.Footnote 77

According to Pares, during the last decade of its activities, the FARC-EP was present in 242 municipalities out of the 1,122 in Colombia.Footnote 78 In 2018, 22 armed groups made up of ex-FARC-EP dissidents were operating in 58 municipalities in 13 departments.Footnote 79 It is estimated that these armed groups have approximately 1,600 combatants, including 1,280 former FARC-EP combatants.Footnote 80

On 28 February 2018, the Office of the Ombudsperson issued

Alerta TempranaFootnote 81 No. 026-18 which indicates the following regarding the presence of FARC-EP dissidents in the country:

- Central-Eastern Colombia: Dissidents of Fronts 1, 3, 7, 16 and 39 are present in the departments of Vaupés and Guaviare, the municipalities of La Macarena and San Vicente del Caguán (Meta), western Cundinamarca, and alongside the Orinoco River on the border with Venezuela.

- Departments of Amazonas, Nariño, Cauca, Caquetá, Huila, Putumayo: Dissidents of Fronts 1, 6, 7, 14, 15, 29, 32, 40, 48, 49 and 63 form groups such as GUP, La Gente del Orden, Los Comuneros and [translation] "others with no clear designation."

- Departments of Arauca and Norte de Santander: Ex-combatants of the FARC-EP's Front 33 have formed dissident groups, particularly in Norte de Santander where they have established ties with an EPL group in the municipality of Tibú.

- Pacific Coast: In the department of Nariño, FARC-EP dissidents are disputing the influence in the Port of Tumaco with the ELN and the AGC. Confrontations with the ELN have intensified in the north of the department of Cauca (including the municipalities of Miranda, Caloto, Corinto, Buenos Aires and Morales), and in the south of Valle del Cauca (including the municipalities of Jamundí, Pradera and Florida).

- The dissidents of the FARC-EP are also reportedly operating in the departments of Boyacá and Casanare.Footnote 82

Pares notes that FARC-EP dissident groups are reportedly engaging in extortion, kidnapping, deploying IEDs against security forces, selling coca paste, and controlling drug trafficking routes, including to Venezuela and Brazil. In the department of Guaviare, FARC-EP dissidents have reportedly limited the access of humanitarian organizations to rural areas.Footnote 83

2.3 Dissidents of the EPL

The EPL emerged in 1967 as the armed wing of the Colombian Communist Party and adopted a Maoist ideology.Footnote 84 InSight Crime indicates that in March 1991, 2,200 members of the EPL demobilized and formed a political party called Hope, Peace and Liberty (Esperanza, Paz y Libertad). However, a group of guerrilla fighters from the EPL rejected the peace agreement and formed a dissident group, which is called "Los Pelusos by authorities."Footnote 85 The dissidents of the EPL are classified by authorities as BACRIM.Footnote 86 Similarly, the ELN considers the EPL a non-revolutionary group due to its ties with narco-paramilitary organizations.Footnote 87 The EPL is commanded by "'Pepe'" (for political matters) and "'Pácora'" (for military matters).Footnote 88 The estimated number of combatants varies among sources, ranging between 200Footnote 89 and 400Footnote 90; most of them are young people under the age of 25 with little military or political training.Footnote 91

Although the dissident movement of the EPL has better weaponry than the ELN due to its ties with drug trafficking organizations, it has less offensive capacity due to the weakening of its structure.Footnote 92 After the death of its leader "Megateo," the EPL failed to consolidate as a group and its structure is made up of small groups, with differences among them.Footnote 93 The EPL is composed of six [translation] "armed commissions" with presence in several municipalities in the department of Norte de Santander, and an "urban commission" in the city of Cúcuta.Footnote 94

2.4 Paramilitary Groups

The precursors of modern paramilitary groups emerged in the 1980s as self-defence groups for drug lords against guerrilla kidnapping and extortion.Footnote 95 In 1997, the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, AUC) emerged as a right-wing umbrella confederation of paramilitary groups operating in Colombia,Footnote 96 with linkages to the army and some political circles.Footnote 97 In 2003, the AUC signed an agreement with the government to demobilize, and although 32,000 paramilitary troops demobilized, some of them joined new paramilitary successor groups, referred to as BACRIM by the government.Footnote 98 These groups continue to engage in widespread abuses such as killings, disappearances and rape.Footnote 99

The Office of the Ombudsperson's

Alerta Temprana No. 026-18 indicates that paramilitary groups are present in [translation] "vast areas" of the departments of Antioquia, Caldas, Casanare, Cauca, Chocó, Córdoba, Guaviare, Magdalena, Meta, Nariño, Putumayo, Risaralda, Sucre, Valle del Cauca, and Vichada, and in the metropolitan area of Cúcuta and the region of Magdalena Medio. There are also a variety of groups that exploit legal and illicit economic activities and are responsible for human rights violations.Footnote 100

The same source indicates the following regarding the presence of paramilitary groups in the country:

- Caribbean region: Los Pancheca, which operates in Santa Marta and Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and has established alliances with paramilitary groups from other regions in Colombia, such as Los Paisas, Águilas Negras and Los Rastrojos, to control territory and trafficking routes along the border with Venezuela, particularly the departments of Guajira, César and Bolívar.

- North-West: Expansion of the AGC in the departments of Chocó, Antioquia, Risaralda and Caldas, where it took over regional organizations such as La Oficina de Envigado and La Cordillera.

- South-West: Presence of the AGC in Valle del Cauca, La Constru in Putumayo, and other local paramilitary organizations in Cauca, Caquetá, Nariño, Putumayo and Valle del Cauca.

- Centre-East: Expansion in the outskirts of metropolitan areas and rural areas of the departments of Meta, Vichada and Guaviare of the AGC, Águilas Negras, Puntilleros, Bloque Meta, Libertadores del Vichada, and Autodefensas de Meta, Guaviare and Vichada.

- North-East: Consolidation of armed groups in Norte de Santander, and dispute of border areas between AGC, Los Rastrojos, and ELN.

- Magdalena Medio: Expansion of the AGC's Bloc Herlin Pinto Duarte and Luis Fernando Gutiérrez Front in the municipalities of Barranco de Loba, San Martín de Loba, Pinillos, Tiquiso, Achí, Montecristo and San Jacinto del Cauca.

- Casanare: Presence of a variety of paramilitary groups, including Autodefensas Campesinas de Casanare, Águilas Negras, Los Carranceros, Renacer de los Buitragueños, Los Rastrojos, Libertadores del Vichada, Bloque Meta and Los Puntilleros.Footnote 101

3. Main Targeted Profiles

According to Human Rights Watch, since the demobilization of the FARC-EP, "[h]uman rights defenders, trade unionists, journalists, indigenous and Afro-Colombian leaders, and other community activists face death threats and violence, mostly from guerrillas and successor groups. Perpetrators of these abuses are rarely held accountable."Footnote 102

The situation of social leaders and human rights advocates is described as [translation] "critical" or "serious" by the Office of the Ombudsperson.Footnote 103 The Office of the Ombudsperson's

Alerta Temprana No. 026-18 listed 345 organizations operating in Colombia that are [translation] "at risk" of violence being committed against them.Footnote 104

The main targeted profiles are of social leaders who denounce the presence of armed groups,Footnote 105 promote the substitution of [illicit] crops, advocate for land restitution, promote the rights of sexual minorities, participate in politics,Footnote 106 advocate for the implementation of the peace accord,Footnote 107 community leaders, former members of the FARC-EP, witnesses before the JEP, and environmentalists.Footnote 108

In its

Alerta Temprana No. 026-18, the Office of the Ombudsperson identified the following as the [translation] "most vulnerable groups" due to their activities in the context of the armed conflict, notwithstanding stating that social leaders in Colombia cover a wide range of areas and a "leader" can refer to individuals who belong to one or more organizations at the local or national levels, for example:

- Communal leader (líder comunal)

- Community leader

(líder comunitario)

- Land restitution leaders

- Leaders of peasant (campesino) organizations

- Leaders of women's organizations

- Leaders of Afro-Colombian organizations

- Indigenous leaders

- Union leaders

- Environmental leaders

- Social leaders

- Leaders of victims and displaced persons

- Leaders of youth organizations

- Leaders of cultural organizations

- Leaders of sexual and gender minorities' organizations

- Leaders of health organizations

- Leaders of artisanal miners

- Human rights advocates and lawyers

- Leaders of NGOs

- Student leaders

- Public servants who work in the area of defending human rights, such as municipal ombudspersons (personeros).Footnote 109

Targeting of these profiles by armed actors is motivated by the drive to eliminate threats to their interests by social leaders whose social/community involvement concerns issues such as:

- Conflicts associated with changes in the use of land and natural resources, including the protection of the environment and the exploitation of mineral resources.

- Implementation of the peace accord [between the national government and the FARC-EP], especially the components on the substitution of illicit crops and the creation of local development plans.

- Land restitution and the return of displaced people to their lands.

- Defense of the land vis-à-vis private interests.

- Complaints or reports related to drug dealing, the presence of armed actors, and the utilization and recruitment of children and adolescents in peripheral areas of urban centres.

- Complaints regarding the use of public funds.

- Access to political participation in elections.Footnote 110

3.1 Statistics on Attacks and Threats

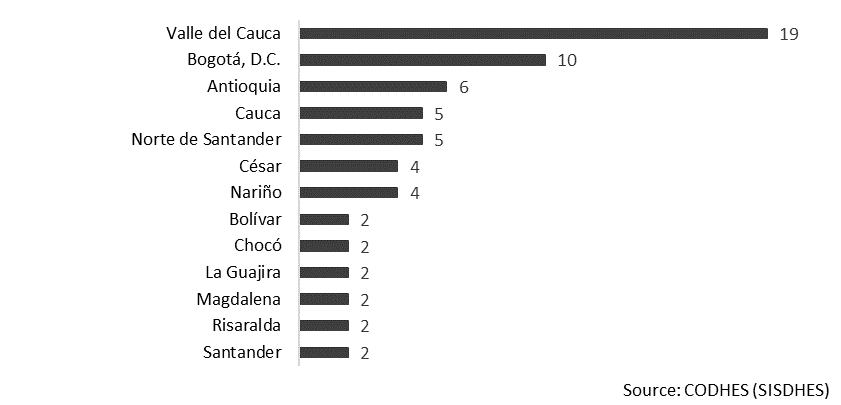

CODHES reported that between 1 January 2019 and 28 February 2019, 72 attacksFootnote 111 were reported against social leaders.Footnote 112 The highest numbers by department are as follows:

Departments with the Highest Number of Repoted Attacks Against Social Leaders 1 January 2019 to 28 February 2019Footnote 113

Alternate format

The image is a bar chart indicating the Colombian departments with the highest number of reported attacks against social leaders from January 1, 2019 to February 28, 2019. The data source is the

Sistema de Información sobre Derechos Humanos y Desplazamiento (SISDHES) of the

Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES).

The number of reported attacks against social leaders for each department are as follows:

- Valle de Cauca: 19 attacks.

- Bogotá, DC: 10 attacks.

- Antioquia: 6 attacks.

- Cauca: 5 attacks.

- Norte de Santander: 5 attacks.

- César: 4 attacks.

- Nariño: 4 attacks.

- Bolívar: 2 attacks.

- Chocó: 2 attacks.

- La Guajira: 2 attacks.

- Magdalena: 2 attacks.

- Risaralda: 2 attacks.

- Santander: 2 attacks.

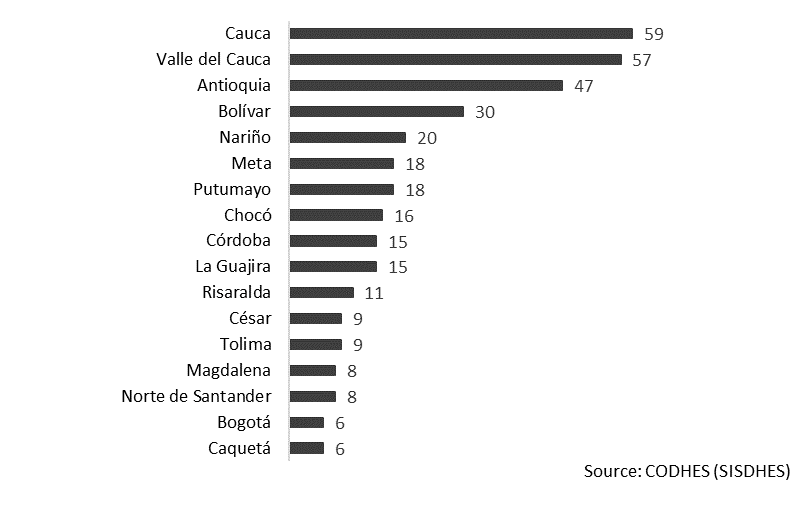

In 2018, 378 attacks were reported against social leaders, including 49 against Afro-Colombians and 94 against indigenous leaders.Footnote 114 The departments with the highest numbers of reported attacks were as follows:

Departments with the Highest Number of Reported Attacks Against Social Leaders 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2018Footnote 115

Alternate format

The image is a bar chart indicating the Colombian departments with the highest number of reported attacks against social leaders from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2018. The data source is the

Sistema de Información sobre Derechos Humanos y Desplazamiento (SISDHES) of the

Consultoría para los Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento (CODHES).

The number of reported attacks against social leaders for each department are as follows:

- Cauca: 59 attacks.

- Valle de Cauca: 57 attacks.

- Antioquia: 47 attacks.

- Bolívar: 30 attacks.

- Nariño: 20 attacks.

- Meta: 18 attacks.

- Putumayo: 18 attacks.

- Chocó: 16 attacks.

- Córdoba: 15 attacks.

- La Guajira: 15 attacks.

- Risaralda: 11 attacks.

- César: 9 attacks.

- Tolima: 9 attacks.

- Magdalena: 8 attacks.

- Norte de Santander: 8 attacks.

- Bogotá: 6 attacks.

- Caquetá: 6 attacks.

In 2017, the Office of the Ombudsperson received 480 complaints regarding threats against social leaders and human rights defenders, the majority of which were in the Urabá region (72), Cauca department (49), Antioquia department (31), Bogotá (28), Magdalena department (27), Cundinamarca department (26), César department (23), Boyacá department (23), Magdalena Medio region (22), and Sucre department (22).Footnote 116

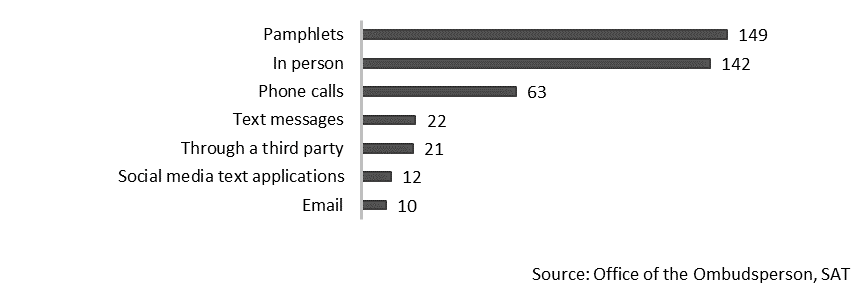

3.1.1 Methods

Threats to targeted persons are issued in different ways. According to the Office of the Ombudsperson, the following were among the ways social leaders received threats reported in 2017:Footnote 117

Alternate format

The image is a bar chart indicating the methods by which social leaders received threats in 2017. The data source is the

Sistema de Alertas Tempranas (SAT) of the Office of the Ombudsperson.

- 149 threats were received through pamphlets.

- 142 threats were received in person.

- 63 threats were received through phone calls.

- 22 treats were received through text messages.

- 21 threats were received through a third party.

- 12 threats were received through social media text applications.

- 10 threats were received by email.

A former official of the Office of the Ombudsperson indicated that, based on her previous work experience, one of the ways armed actors threaten people is by visiting them and informing them that they have a certain amount of time to leave. The same source also indicated that threats against some teachers have consisted of the delivering of funeral wreaths, sometimes to their schools.Footnote 118

3.2 Killings

The Office of the Ombudsperson indicates that 462 social leaders and human rights advocates were killed between 1 January 2016 and 28 February 2019.Footnote 119

CODHES reported the killing of 24 social leaders between 1 January 2019 and 28 February 2019. The numbers of homicides of social leaders by department were as follows: Antioquia (5), Nariño (4), Norte de Santander (3), Valle del Cauca (2), and Bolívar, Caquetá, Cauca, Chocó, Córdoba, La Guajira, Magdalena, Meta, Putumayo and Santander (1 each).Footnote 120 In 2018, 145 killings were reported against social leaders, including 21 against Afro-Colombians and 30 against indigenous leaders.Footnote 121 The killings took place in the following departments:

Killings of Social Leaders in 2018 by DepartmentFootnote 122

| Department | Number of Homicides of Social Leaders |

|---|

| Antioquia | 30 |

| Cauca | 26 |

| Putumayo | 15 |

| Córdoba | 10 |

| Nariño | 8 |

| Valle del Cauca | 8 |

| Norte de Santander | 7 |

| Meta | 6 |

| Caquetá | 5 |

| César | 4 |

| Chocó | 4 |

| Bolívar | 3 |

| Sucre | 3 |

| Huila | 2 |

| Magdalena | 2 |

| Quindío | 2 |

| Tolima | 2 |

| Arauca | 1 |

| Atlántico | 1 |

| Boyacá | 1 |

| Guaviare | 1 |

| La Guajira | 1 |

| Risaralda | 1 |

| Santander | 1 |

| Vichada | 1 |

|

Total |

145 |

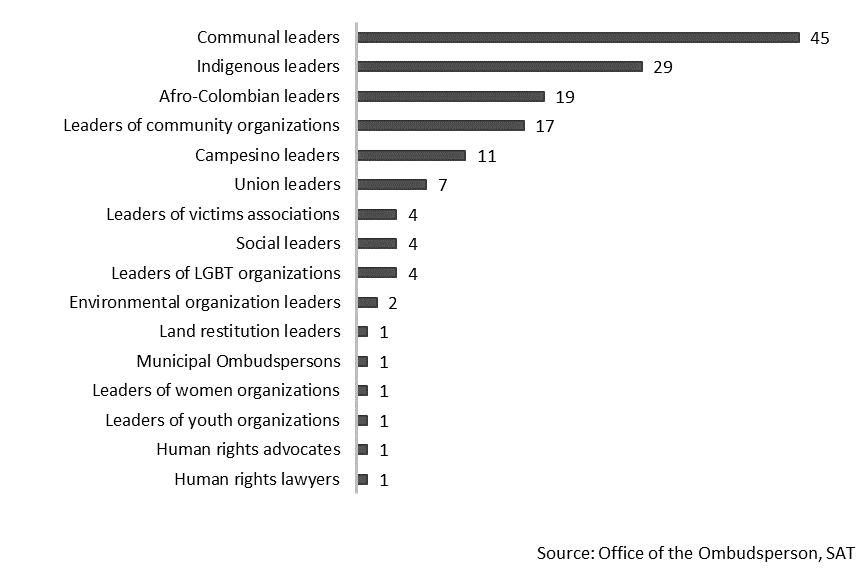

The Office of the Ombudsperson's

Alerta Temprana No. 026-18 indicates that between 1 January 2017 and 27 February 2018, 148 social leaders were killed in the country.Footnote 123

Number of Homicides of Social Leaders 1 January 2017 to 27 February 2018Footnote 124

Alternate format

The image is a bar chart indicating the number of homicides of social leaders, by category of social leaders, from January 1, 2017 to February 27, 2018. The data source is the

Sistema de Alertas Tempranas (SAT) of the Office of the Ombudsperson. The number of homicides are as follows:

- Communal leaders: 45 homicides.

- Indigenous leaders: 29 homicides.

- Afro-Colombian leaders: 19 homicides.

- Leaders of community organizations: 17 homicides.

- Campesino leaders: 11 homicides.

- Union leaders: 7 homicides.

- Leaders of victims associations: 4 homicides.

- Social leaders: 4 homicides.

- Leaders of LGBT organizations: 4 homicides.

- Environmental organization leaders: 2 homicides.

- Land restitution leaders: 1 homicide.

- Municipal Ombudspersons: 1 homicide.

- Leaders of women organizations: 1 homicide.

- Leaders of youth organizations: 1 homicide.

- Human rights advocates: 1 homicide.

- Human rights lawyers: 1 homicide.

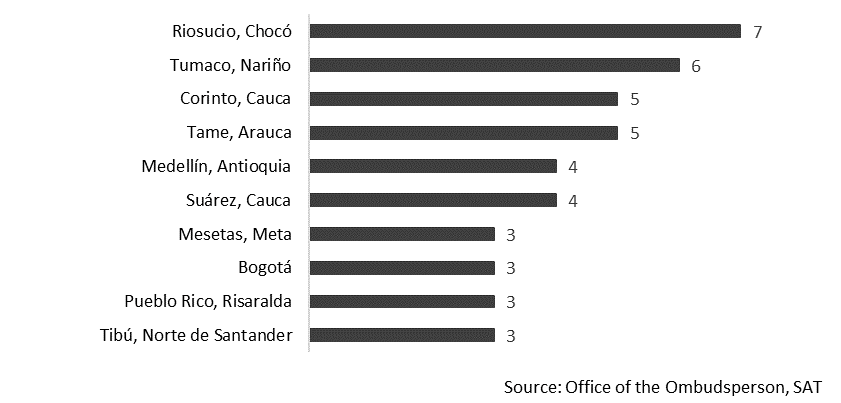

The majority of homicides occurred in remote rural areas (47), followed by rural areas (36), semi-rural areas (33), metropolitan districts (18), and cities (14).Footnote 125 The municipalities with the highest number of homicides of social leaders during the same period were as follows:

Localities with the Highest Number of Homicides of Social Leaders January 2017 to February 2018Footnote 126

Alternate format

The image is a bar chart indicating the number of homicides committed against social leaders in the localities where the number of homicides is the highest, from January 2017 to February 2018. The data source is the

Sistema de Alertas Tempranas (SAT) of the Office of the Ombudsperson.

The number of homicides of social leaders in each locality are the following:

- Riosucio, Chocó: 7 homicides.

- Tumaco, Nariño: 6 homicides.

- Corinto, Cauca: 5 homicides.

- Tame, Arauca: 5 homicides.

- Medellín, Antioquia: 4 homicides.

- Suárez, Cauca: 4 homicides.

- Mesetas, Meta: 3 homicides.

- Bogotá: 3 homicides.

- Pueblo Rico, Risaralda: 3 homicides.

- Tibú, Norte de Santander: 3 homicides.

Bolívar, Cartagena and Cúcuta, Norte de Santander each had 2 homicides recorded for the same period of January 2017 to February 2018.Footnote 127

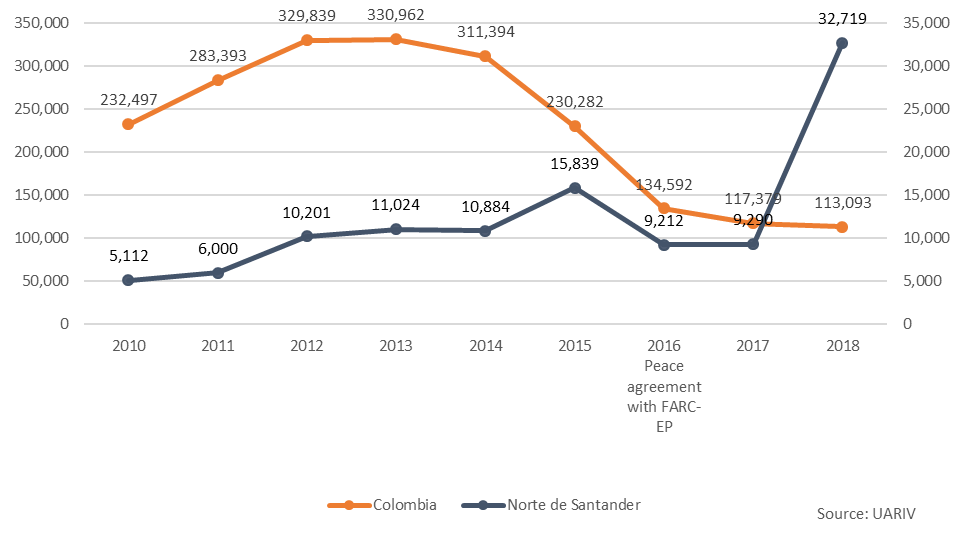

4. Displacement

According to Human Rights Watch, Colombia has had a long history of displacement: "[v]iolence associated with the conflict has forcibly displaced more than 7.7 million Colombians since 1985, generating the world’s largest population of internally displaced persons (IDPs)."Footnote 128

The representative from the Victim Assistance and Comprehensive Reparation Unit (Unidad para la Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas, UARIV) explained that displacement is a phenomenon that is difficult to detect in part because some people do not file complaints and because some consider it a [translation] "common" occurrence. Forced displacement occurs more often in rural areas. However, there is significant underreporting of urban displacement because this type of displacement is more [translation] "surreptitious" and people prefer to remain silent about it.Footnote 129

According to the OCHA, the causes of mass displacement in 2018 included confrontations among armed actors not involving the armed forces (32 percent), confrontations between the ELN and EPL (33 percent), unilateral actions by the ELN (7 percent), confrontations among armed actors involving the armed forces (7 percent), unknown actors (7 percent), unilateral actions by the dissidents of the EPL (5 percent), unilateral actions by the dissidents of the FARC-EP (3 percent), and other armed groups (6 percent).Footnote 130

Targeted individuals often move between urban areas.Footnote 131 In affected communities in the Pacific coast area, for example, when an armed actor creates displacement, displaced persons move for short periods of time with relatives or friends living in neighbouring areas and eventually go back to their communities.Footnote 132 There have been reports of persons being threatened or killed when they return to their place of origin.Footnote 133

In urban and metropolitan areas, paramilitary groups operate through local gangs, which have the knowledge of the territory and the capacity to monitor and exercise control of the places where these gangs operate.Footnote 134

It is estimated that approximately 60,000 people were displaced in 2018, the lowest figure since 1994 and approximately 10 percent as much as in 2002, considered the [translation] "worst year" of the conflict, during which 700,000 people were forcibly displaced.Footnote 135

Internal Mass Displacement by Year, Numbers and Department, According to the Office of the OmbudspersonFootnote 136

| Year | Mass Displacements | People Displaced | Families Displaced | Departments |

|---|

| 2017 | 51 | 12,841 | 3.602 | Antioquia, Cauca, Chocó, Córdoba, Nariño, Norte de Santander, Risaralda, Tolima, Valle del Cauca. |

| 2018 | 95 | 32,190 | 9,670 | Antioquia, Arauca, Cauca, Chocó, Córdoba, Guaviare, Meta, Nariño, Norte de Santander, Putumayo, Valle del Cauca. |

| [January-February] 2019 | 8 | 2,567 | 824 | Antioquia, Cauca, Magdalena, Nariño, Norte de Santander. |

Internal Mass Displacement by Numbers and Department Between 1 January and 28 February 2019, According to CODHESFootnote 137

| Department | Number of Displacement Events | People Displaced | Families Displaced |

|---|

|

Total |

24 |

9,831 |

2,039 |

| Nariño | 7 | 816 | 176 |

| Antioquia | 6 | 6,979 | 1,405 |

| Norte de Santander | 4 | 1,689 | 376 |

| Chocó | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Caquetá | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cauca | 1 | 200 | 50 |

| Tolima | 1 | 25 | 5 |

| Valle del Cauca | 1 | 108 | 21 |

| Bolívar | 1 | 10 | 2 |

Internal Mass Displacement by Numbers and Department Between 1 January and 31 December 2018, According to CODHESFootnote 138

| Department | Number of Displpacement Events | People Displaced | Families Displaced |

|---|

|

Total |

184 |

53,650 |

13,326 |

| Norte de Santander | 50 | 16,286 | 4,394 |

| Nariño | 41 | 9,882 | 2,480 |

| Antioquia | 39 | 13,947 | 3,447 |

| Chocó | 12 | 2,566 | 526 |

| Córdoba | 10 | 2,475 | 630 |

| Valle del Cauca | 8 | 4,638 | 955 |

| Cauca | 5 | 2,640 | 637 |

| Putumayo | 5 | 51 | 13 |

| Bolívar | 4 | 25 | 5 |

| Arauca | 1 | 60 | 15 |

| Boyacá | 1 | 15 | 3 |

| Caquetá | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| César | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Guaviare | 1 | 70 | 18 |

| Huila | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| Magdalena | 1 | 86 | 19 |

| Meta | 1 | 50 | 13 |

| Risaralda | 1 | 850 | 170 |

| Tolima | 1 | 1 | 0 |

The Office of the Ombudsperson indicates that displacement also occurs after a social leader is killed. After the killing of Plinio Pulgarín Villadiego, the president-elect of the communal association of Alto Mira San Pedrito (Córdoba), in January 2018, an unidentified armed group summoned its inhabitants to tell them that they had to leave the town by noon. As a result, 425 persons from 133 families from the area were displaced.Footnote 139

5. Protection

5.1 Victims and Land Restitution Law (Ley de Víctimas y Restitución de Tierras, LVRT)

Law 1448 of 2011, also known as the

LVRT, entered into force on 10 June 2011 to provide assistance and reparation to persons who, individually or collectively, have been victims of the armed conflict since 1 January 1985.Footnote 140 The

LVRT covers persons who, in the context of the armed conflict, have been victims of the following:

- forced dispossession of lands;

- terrorist acts, attacks, combats, clashes, and assaults;

- threats;

- sexual violence during an armed confrontation;

- forced disappearance;

- forced displacement;

- homicides and massacres;

- landmines, unexploded munitions, and improvised explosive devices;

- kidnapping;

- torture;

- child recruitment;

- bodily injury; and

- psychological mistreatment.Footnote 141

The

LVRT provides for the following assistance to persons recognized as victims:

- Humanitarian assistance, which includes the provision of food, personal hygiene needs, temporary housing and transportation, and emergency medical and psychological assistance.

- Access to elementary and middle schooling, as well as lines of credit with the Colombian Institute of Educational Credit and Technical Studies Abroad (Instituto Colombiano de Crédito Educativo y Estudios Técnicos en el Exterior, ICETEX) to pursue post-secondary studies.

- Access to healthcare and services such as hospitalization, medicines, laboratory tests, imaging, transportation, sexual and reproductive rights, and abortion under the terms stipulated by Colombian law.Footnote 142

Additionally, the

LVRT provides emergency humanitarian assistance to persons who have become victims within the previous three months [preceding their declaration]Footnote 143 and provide a declaration before the Public Ministry (Ministerio Público).Footnote 144 The emergency assistance consists of temporary shelter, food assistance, and assistance to return to the place of origin or relocation.Footnote 145

5.2 Victim Assistance and Comprehensive Reparation Unit (UARIV)

The

LVRT created the UARIV, which coordinates the National System for Comprehensive Victim Support and Reparation (Sistema Nacional de Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas, SNARIV)Footnote 146 and the resources allocated to provide assistance and reparations to victims of the armed conflict.Footnote 147

5.2.1 Assistance Provided to Victims

In order to access benefits under the

LVRT, the person must be registered with the Registry of Victims (see section 5.2.2).Footnote 148 Assistance consists of five components: rehabilitation, compensation, reparation, restitution, and guarantees of no repetition.Footnote 149

Rehabilitation: Includes psychological assistance for adults, adolescents and children between 6 and 12 years old. It also provides psychological and social assistance for victims who live in other countries through sessions organized by the UARIV. During sessions, the UARIV carries out symbolic acts to give letters of acknowledgement (cartas de dignificación) to victims. This component also provides psychological support to the families of victims of homicide and forced disappearance, including during the search and return of bodies.Footnote 150

Compensation: Consists of a monetary payment made to the victim or the family of the victim, according to the type of the crime committed against them, as follows:Footnote 151

| Victimizing Act | Amount in COP | Payable to |

|---|

| Homicide | 40 SMLMVFootnote 152 | Family members |

| Forced disappearance | 40 SMLMV | Family members |

| Kidnapping | 40 SMLMV | Victim after being released |

| Injuries with permanent disability | Up to 40 SMLMV | Victim |

| Injuries that led to [temporary] disability | Up to 30 SMLMV | Victim |

| Recruitment of children and adolescents | 30 SMLMV | Victim |

| Sexual violence, including children and adolescents born from a rape during the armed conflict | 30 SMLMV | Victim |

| Torture or cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment | 10 SMLMV;up to 40 SMLMV if the person sustained injuries | Victim |

| Forced displacement | Between 17 and 27 SMLMVs, up to 40 SMLMVs if the person sustained more than one of the violence act covered | Victims and their families |

Someone who is a victim of multiple violations can receive a maximum total compensation of 40 SMLMV.Footnote 153

Reparation: Consists of measures aimed at [translation] "rebuilding the truth, promoting historical memory and dignifying the victims." These measures include the issuing of letters of acknowledgement and compensation letters, which recognize the condition of the addressee as a [translation] "victim"; exemption from compulsory military service, or cessation if already serving in the military; assistance in the search for disappeared relatives, or identification of the bodies of relatives found; and support to carry out local initiatives related to the commemoration of historical memory.Footnote 154

Restitution: Consists of providing the victim with reparation and restitution of land, housing, lines of credit, and training. It also provides assistance to return to the place from where the victim was displaced, relocation to another part of the country, and integration into the new area of residence.Footnote 155

Guarantees of no repetition: Consists of measures to prevent further violation of victims' rights and [translation] "eliminate and overcome the structural causes of mass violations of human rights." It consists of programs such as demining, prevention of forced recruitment, education on human rights, and effective application of these measures.Footnote 156

A document produced by the UARIV indicates that the UARIV also provides [translation] "humanitarian assistance" to Colombians returning from abroad to re-establish residence. This assistance is provided only to persons who were victims of forced displacement. The assistance can be requested at either a Colombian consulate abroad or at any of the UARIV offices in Colombia.Footnote 157

5.2.2 Registry of Victims

The UARIV manages the Registry of Victims (Registro Único de Víctimas, RUV), which was created in 2011 with the