Report of Results

Prepared by:

Planning, Evaluation and Performance Measurement Directorate

Context

This report describes the results of the measurement of quality in decision-making in the Refugee Protection Division (RPD). Performance is assessed against the key indicators of quality that align with the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada’s (IRB) overall expected results for decision-making excellence:

- Timely and complete pre-proceeding readiness

- Respectful proceedings

- Focused proceedings

- Clear, complete, concise and timely decisions

The study reviewed 119 out of a possible 596 claims and applications finalized in June 2016 on their merits after an oral hearing before a single-member panel. The files were randomly selected in proportion to region, outcome, language of proceeding, oral and written decisions, and in-person or in-writing ministerial intervention. Out of a possible 78 members, 77 are found in the sampling. Results are accurate to within 7 percent, 9 times out of 10. This margin increases when data is broken down by region or case type. However, the goal of the study was not to generate statistics but to identify areas of strength, concern, and patterns in decision-making quality.

The files were reviewed by two evaluators who are former members of the

RPD and former consultants to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The evaluators examined all evidentiary and administrative materials on file, listened to the complete audio recordings and assessed these against qualitative indicators in a checklist developed by the Planning, Evaluation and Performance Measurement Directorate and approved by the Chairperson (see

Appendix). Each indicator is assessed along either a 1-to-3 rating scale or a binary yes-no scale.

Two different targets are applied in the assessments:

- “Meets expectations” is represented as “2” on the 1-to-3 scale.

- Results are also expressed as a

percentage of cases that scored at least “2”. For example, 70% is the target for indicator

#11 (The member ensures the parties focus testimony and documentation on the issues that the member has identified as the relevant issues), meaning that 70% of the files are expected to score 2 or higher against this indicator.

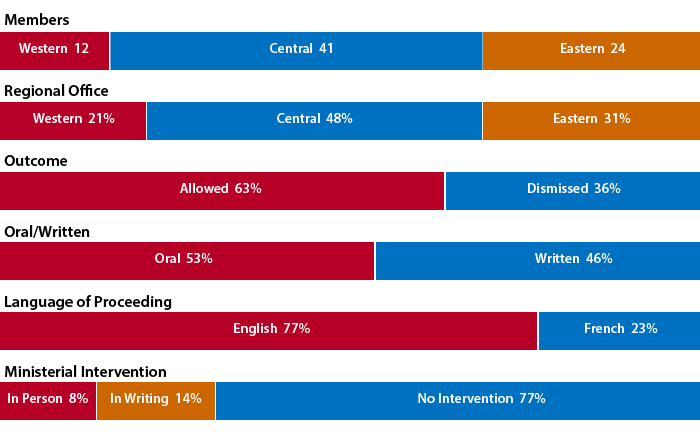

The following charts illustrate the sampling makeup:

[Alternate format]

Members

- Western: 12

- Central: 41

- Eastern: 24

Regional Office

- Western: 21%

- Central: 48%

- Eastern: 31%

Outcome

- Allowed: 63%

- Dismissed: 36%

Oral/Written

Language of Proceeding

Ministerial Intervention

- In Person: 8%

- In Writing: 14%

- No Intervention: 77%

This study acknowledges the inherent limitations to qualitative research, which does not generate precise data as does quantitative research. Moreover, a small sample size limits the inferences that may be made about the broader caseload. The findings in this report are solely those of the evaluation team. Their observations are necessarily subjective in nature and do not lend themselves to firm conclusions on legal matters such as the correct application of the law, the weighing of the evidence, or the fairness of the proceedings from a natural justice perspective. Only a court reviewing the case can arrive at such conclusions. This report aims to provide a perspective to improve the Division’s performance overall.

2.0 Performance Results

2.1 Timely and complete pre-proceeding readiness

Why measure this:

The groundwork for a quality hearing and decision is set when the Registry prepares a timely, organized and complete case docket and the member assimilates the facts and key issues of the case.

What was measured

| | Average score out of 3 (target 2.0) | Percentage of cases scoring at least 2.0 |

|---|

| #1 The file was provided to the member no later than 8 days prior to the proceeding. | 2.6 | 82% |

| #2 The file contains all required information and documents. | 2.9 | 94% |

| #3 The file was organized in a logical and standardized manner. | 2.9 | 95% |

| #4 The recording and file indicate that the member was ready for the proceeding. | 2.1 | 90% |

| Targets: Respectively 80%, 90%, 100% and 100% of cases achieving at least 2.0 out of 3. |

What the numbers say:

- The Registry delivered the docket within the 8-day requirement 82% of the time, comparable to previous years

- About 95% of files were properly organized or complete with all the required information

- All results in

#1 to

#4 are consistent across the three regions and with results from the previous study

Strengths

Docket preparation. Overall, the Registry delivered a docket to the member that was timely, organized and complete with all the required documents in 75% (n=89) of the cases. Of the remaining 30 cases, 22 were scored a “1”, the most common reason being delivery of the docket to the member less than 8 days before the hearing. Missing documents or an unorganized docket round out the remaining cases.

The reasons for docket lateness were not examined, but may have included circumstances beyond the

IRB’s control, such as last-minute applications, which are routed to the Assistant Deputy Chairperson, and member unavailability.

Member preparedness. The study found that in 90% (n=112) of the cases, the member was adequately prepared for the hearing. Results were highest in the Western and Central Regions. This finding is based on members having prepared an exhibit sheet, setting a hearing agenda, or referring to evidence on file during claimant testimony. In observing a prime example of member preparedness, the evaluator wrote:

Excellent introduction in that she got through the preliminaries quickly and efficiently. Her exhibit list had been prepared in advance and counsel had had a chance to review it. During questions, she referred to parts of the documentary evidence to get a reaction from the claimant demonstrating that she was in good command of the material before her.

Opportunities

Member preparedness. Twelve cases were scored a “1” for member preparedness. A number of reasons form the basis of the scoring, including that the member: (1) did not cite the key issues at the start of the hearing, (2) was slow and hesitant in questioning, and (3) demonstrated that they were unaware that certain documents were included in the disclosures when in fact they had already been admitted into evidence. In one such case, the evaluator observed:

A second example of the member not being as prepared as one would expect happens around the 1 hour 8 minute mark when he asks the principal claimant if she has the arrest warrant and when she hesitates, he is annoyed and states, "I'm asking you a question" at which point she offers that she gave it to her lawyer. The warrant was, in fact, in Exhibit 7 and had the member reviewed the documents carefully, he would have known this.

Momentarily forgetting the details of an exhibit is not unusual, but as the evaluator further noted, “an apology for being so abrupt with the claimant would have been appropriate”.

Inconsistent record. While 94% (n=112) of dockets had all the required documentation and information, in a few cases that information was not internally consistent. This is especially true of the Hearing Disposition Record (HDR), which members fill in with the details of a completed sitting, such as the hearing date, disposition, and names of participants.

In all quality studies, incorrect

HDR information has been a recurring finding. In one instance, the

HDR recorded that the member disallowed late documents, yet nothing in the audio recording or elsewhere in the docket indicated that the claimant provided late disclosure, and all documents were on file. In another case, the multiple sitting dates for one claim did not match the dates on the cover page of the reasons for decision.

Of greater concern, in another hearing that took place in September 2015 the audio recording revealed that the member scheduled a resumption date in October 2015 to allow counsel to complete the examination and provide submissions. However, the member noted in the

HDR that the decision was reserved. The resumption did not take place. Counsel requested the resumption in February 2016, but without any documentation on file to explain events the member rendered a decision in June 2016, in favour of the claimant.

In a case that was described as reserved on the

HDR, the member received post-hearing disclosure without an application from the Minister. In the end, the member relied on the Minister’s document to make findings and deny the claim on an exclusion ground.

These cases illustrate the importance of recording correct information in the

HDR. In the period following the conclusion of a hearing when new hearings quickly overtake people’s attention, correct

HDR information guides members and Registry staff on the required next steps in managing a particular claim.

Recommendation

A communiqué or a professional development session could remind members of the importance of correctly recording and using the information in the Hearing Disposition Record.

2.2 Respectful proceedings

Why measure this:

Individuals appearing before the

IRB expect that they will be treated with sensitivity and respect. Any shortcoming in this regard potentially undermines tribunal integrity and public confidence. Indicators

#5 and

#6 are applied to all cases while

#7,

#8 and

#9 are scored on an as-applicable basis.

What was measured

| | Average score out of 3 (target 2.0) | Percentage of cases scoring at least 2.0 |

|---|

| #5 The member treats participants with sensitivity and respect. | 2.0 | 92% |

| #6 The member ensures parties have an opportunity to present and respond to evidence and to make representations. | 2.0 | 96% |

| #7 The member identifies when the evidence has not adequately addressed an important issue as identified by the member and asks questions of clarification. | 2.1 | 92% |

| #8 Communications in the absence of a party is disclosed and summarized on the record. | n/a | n/a |

| #9 Problems with interpretation are identified and addressed. | 1.9 | 75% |

| Target: 100% of cases achieving at least 2.0 out of 3. |

What the numbers say:

- All average scores meet or exceed the target

- Scores are consistent regionally in

#5 and

#6, which were assessed in all cases

- No cases were found applicable under

#8 and 12 were applicable under

#9

Strengths

Sensitivity and respect. In 92% (n=109) of the cases, the members treated the parties in a sensitive and respectful manner. This included challenging hearings that saw claimants giving highly emotional testimony and claimants designated as vulnerable. In two hearings, the evaluator observed what was true of members across most cases:

Member is considerate of claimant when she breaks down at one point. Member's concern and attitude assists in helping claimant continue.

The tone of her voice and the way she speaks to the claimant are measured and professional.

Questions of clarification. In 92% (n=49) of the 52 applicable claims, members asked clarification questions when the evidence became unclear or insufficient in relation to one of the issues. In notable examples, the member worked in tandem with counsel to elicit the needed testimony from the claimant.

Member solicits assistance of counsel when claimant has difficulty understanding her questions. Develops good relationship with counsel in order to clarify evidence.

Late in the hearing she picks up on an issue that was not mentioned in the BOC [Basis of Claim Form] and seeks counsel's assistance in exploring this issue.

-

Communication not on the record. Although no instances of

ex parte communication were found under indicator

#8, the study found two cases of off-the-record communication. In the first, the member and counsel engaged in a discussion outside the hearing room after the first sitting, leading to an application for the member to recuse herself. In the other case, multiple off-the-record conversations took place between the member and counsel, and in each situation the member summarized the information on the record.

Opportunities

Sensitivity and respect. In 8% (n=10) of the cases, the evaluators scored members a “1” for not meeting expectations for a hearing conducted with sensitivity and respect. In these cases, which came from all three regions, the audio recordings revealed members confronted by claimants who were demonstrably challenging and frustrating. However, the members responded with a change in tone that betrayed annoyance or impatience with the claimant. In one hearing, an evaluator notes:

Member at several points talks about not wanting to upset the claimant and that he needs information to make a decision but he does not seem sensitive to how the hearing is developing because of his tone and the way he is relating to the claimant. At various points he stops to say he is asking simple questions and shows his annoyance at how the claimant is answering.

In other examples, as questioning became repetitive, different members:

- admonished the claimant for not having left a domestic abuse situation;

- chided the claimant for not going online to research asylum, working illegally and cheating in his relationships;

- gave cause to the claimant to plead for the member not be angry at him; and,

- accused the claimant of “lying to me”.

The evaluators recognize that these were not easy hearings for the member, but also made the observation generalizable to all cases that, “Accusatory questions like that one do nothing to keep the lines of communication open in a refugee hearing.”

-

Presenting and responding to evidence. In 96% (n=114) of the cases, claimants were afforded the opportunity to present evidence and respond to the issues raised by the member or the other party. In fact, in many of these cases the only examination was the member’s, and counsel submissions were waived. In the few cases that scored a “1”, the impact was potentially high given the reasons cited by the evaluators:

- The member tabled a Response to Information Request that was released one day before the hearing. The audio recording did not indicate that the unrepresented claimant was given an opportunity to read the document.

- After the decision was reserved, the Minister provided post-hearing disclosure without an application for doing so as set out in Rule 43 (1).Footnote 1 Rather than invite submissions to allow or reject the document or to give counsel the opportunity to respond, the member entered it in evidence and cited it and similar exhibits to reject the claim on an exclusion ground.

- The member initially denied the Minister’s request to reply to counsel’s submissions in order not to prolong the hearing. Only after insisting on his right of reply was counsel for the Minister allowed to proceed.

Recommendation

When considering professional development programming, the division should consider the above findings on sensitivity and respect and responding to adverse evidence.

-

Interpretation. The study found 8 cases with interpretation problems requiring the member to intervene to protect the fairness of the proceeding. In 6 of the 8 cases, the member resolved the situation calmly and quickly by identifying the issue in consultation with the hearing participants and then either giving fresh directions to the interpreter or claimant, or deciding to order a different interpreter. However, in 2 cases the member could have managed the situation in a different manner. In the first, the member recorded “crap interpreter” in the

HDR, adjourned the hearing, and left no explanation in either the

HDR or audio recording as to how the interpretation may have impaired the proceeding. In another case, counsel brought forth an application to remove the interpreter after the claimant and an observer, both of whom had functional English, expressed concerns about the interpretation. The member suggested, and counsel agreed, that the claimant and observer assist the interpreter by ensuring that the testimony was reflected in the interpretation. The evaluator observes that while the member had reason to finish up the hearing and was leaning in the claimant’s favour, “as a general principle, it is not a good idea to engage one of the claimants and/or an observer to assist in interpretation.” The impartiality and independence of the interpretation may otherwise be compromised.

2.3 Focused proceedings

Why measure this:

Proceedings that are efficient and well managed create conditions for quality outcomes to emerge and support the

IRB’s efforts to make the most effective use of its resources. Indicators

#10 to

#12 are assessed against all cases while

#13 to

#20 are assessed on an as-applicable basis.

What was measured

| | Average score out of 3 (target 2.0) | Percentage of cases scoring at least 2.0 |

|---|

| #10 The member sets the issue agenda or confirms consent of the parties to the agenda at the start of the proceeding. | 1.9 | 80% |

| #11 The member ensures the parties focus testimony and documentation on the issues that the member has identified as the relevant issues. | 1.9 | 81% |

| #12 Did the hearing complete in the time allotted? | 2.6 | 82% |

| #13 The member's questioning is relevant in relation to the issues identified in the hearing agenda or issues identified in the course of the hearing. | 2.0 | 86% |

| #14 The member's questioning is focused and organized. | 2.0 | 88% |

| #15 The member manages challenging situations as they arise. | 1.8 | 65% |

| #16 During the course of the hearing, the member narrowed the issues. | 1.9 | 67% |

| #17 The member narrows the issues for final representations. | 1.8 | 58% |

| #18 The member accommodates needs of vulnerable participants, including unaccompanied minors, to facilitate their presentation of evidence. | 2.0 | 100% |

| #19 Member deals with oral applications made by parties. | 2.0 | 100% |

| #20 Member identifies applicable legislation, regulations, Rules or Guidelines. | 1.7 | 43% |

| Target: 70% of cases achieving at least 2.0 out of 3. |

What the numbers say:

- All scores in

#10,

#11,

#12,

#13, and

#14 are consistent with previous years; in other questions the sample of applicable cases was too small to generalize

- The highest performing indicator is

#12, which improved by nearly one point from 1.8 to 2.6 from the previous study

Strengths

-

Issue agenda. In the Central and Western Regions, members started the hearing with an issue agenda 95% and 88% of the time respectively. This exceeds the target of 70% but is short of the 100% scores when quality was first assessed in 2013-14. The Eastern Region achieved 54%, and is addressed further below.

-

Vulnerable persons. The study found that in the 3 proceedings involving vulnerable persons, including unaccompanied minors, the members showed sensitivity and patience to facilitate testimony. In cases where an application was made to formally identify the claimant as vulnerable, procedural accommodation was granted, including reverse order of questioning and frequent breaks.

-

Member’s questioning. In nearly 90% of the hearings the members’ questioning was both relevant to the issues cited in the claim and conducted with a sense of organized purpose. What set these cases apart from the nearly 15 cases that scored below expectations were sound courtroom practices:

- setting out an issue agenda and following it;

- a chronological or other methodical order to the questions;

- use of headlines to signal transition to a different issue;

- open-ended questions and follow-up probing; and

- one claimant testifying at a time (as opposed to allowing spouses to jump in)

-

Expeditious hearings. Among all cases finalized in June 2016 within and outside the sampling, hearings were concluded within a median time of 2 hours and 10 minutes, well within the target of one half-day. Compared to the previous study 2 years earlier of what was then a still new division, hearings now are 45 minutes shorter and more consistent in duration across the regions. That study had also found that when good practices—preparing before the hearing, setting an agenda, focusing the questions and narrowing the issues—were not observed, hearings grew longer. In this year’s study, however, the data counterintuitively showed that hearing duration was largely unaffected when members did not observe these courtroom practices. Hearings still managed to average 45 minutes less, suggesting that other adjudication strategies or member experience are accounting for shorter hearings. Several recordings also suggest that members and counsel have become familiar with each other’s styles and approaches in the hearing room.

Opportunities

-

Issue agenda. In 54% (n=20) of the 37 cases in the Eastern Region, the member started the hearing with an issue agenda or a discussion with counsel of the expectations for how the hearing would unfold, as set out in

Chairperson Guideline 7.Footnote 2 This represents a decline from 83% when quality was last measured in 2014-15. In these cases, the hearing jumped immediately to the examination of the claimant. While the only issue may have been credibility, stating as such at the beginning may have permitted the claimant to better understand what the member needed to hear to make a decision.

- In some cases members formed the issue agenda at the hearing and added issues that took counsel by surprise. In two such cases, the member added exclusion and internal flight alternative, explaining that these issues interested the Minister, as opposed to the member. Counsel expressed concern since no notice of intervention on these grounds was received, and the Minister was not participating in person to make arguments.

Recommendation

Members should be reminded of the requirement in Guideline 7 of consulting counsel about the issues and identifying expectations regarding how the hearing should unfold.

Focusing on relevant issues. Keeping the questions and answers focused on the issues the member deems relevant allows for a more efficient and effective hearing to unfold. In this regard, as 20% of members did not establish the issues at the outset, roughly 20% of the time the testimony was unanchored to any declared agenda. Other cases were marked by repetitive questioning between the member and counsel and verbose witnesses. However, 8% (n=10) of the cases scored a “3”. In these situations, members were typically confronted by difficult witnesses and deftly controlled the hearing to keep it on track. As the evaluator observes of one case:

In answers, the claimant often strayed from the question to provide information that either the member did not need or did not want at that point in her examination of the claim. She was very good at ensuring claimant stayed focused on the question before her and she did this in a very even handed way and never became frustrated with the claimant (or if she did, she never showed it).

2.4 Reasons state conclusions on all determinative issues

Why measure this:

The Supreme Court of Canada set the requirement for justifiability, intelligibility and transparency in a decision of an administrative tribunal.Footnote 3 Through indicators

#21 to

#31 on the following three pages, this study applies the Court’s requirement in the context of

IRB decision-making.

What was measured

| | Average score out of 3 (target 2.0) | Percentage of cases scoring at least 2.0 |

|---|

| #21 Issues identified as determinative at the hearing are dealt with in the reasons. | 2.0 | 88% |

| #22 Conclusions are based on the issues and evidence adduced during the proceedings. | 2.1 | 91% |

| Target: 95% of cases achieving at least 2.0 out of 3 |

What the number say:

- Results are consistent with previous years and fall within target or the margin of error

- Eastern Region numbers are lower than other regions due to

#21 and

#22 being dependent on

#10—if issues are not initially identified, latter scores inevitably fall

Determinative issues. Members collectively met the target or fell within the margin of error for addressing all determinative issues based on the evidence adduced.

Of the 119 reasons, 14 did not deal with all the issues identified as determinative at the outset. Of these 14 cases, 12 reasons did not deal with the issues, because the member did not explicitly identify the issues at any time. While the key determinative issues could usually be inferred by the member’s questions, it is only in the reasons that the issues were declared for the first time. It may be noteworthy that 5 of those reasons supported a rejected claim.

2.4.1 Decisions provide findings and analysis necessary to justify conclusions

What was measured

| | Average score out of 3 (target 2.0) | Percentage of cases scoring at least 2.0 |

|---|

| #23 The member makes clear, unambiguous findings of fact. | 2.1 | 96% |

| #24 The member supports findings of fact with clear examples of evidence shown to be probative of these findings. | 2.1 | 93% |

| #25 The member bases findings on evidence established as credible and trustworthy. | 2.1 | 96% |

| #26 The member addresses parties’ evidence that runs contrary to the member’s decision, and why certain evidence was preferred. | 2.1 | 88% |

| #27 The member identifies legislation, rules, regulations, Jurisprudential Guides, Chairperson’s Guidelines or persuasive decisions where appropriate. | 2.6 | 84% |

| #28 The member takes into account social and cultural contextual factors in assessing witnesses’ testimony. | 2.0 | 86% |

| Target: 95% of cases achieving at least 2.0 out of 3 |

What the numbers say:

- All results are consistent across the regions and compared to previous years

- The 3 universally applicable indicators—#23,

#24 and

#25—which are key to any reasons analysis, score highest

Strengths

Detailed analysis. The study found that in 93% (n=111) of the reasons, the members met or exceeded expectations against indicators

#23,

#24 and

#25—the three compulsory elements for findings and analysis that justify the conclusions. In the strongest examples, the evaluators found that the members were explicit in their findings and connected those findings to specific locations in the evidence, which they also explained why was credible and trustworthy:

Excellent use of documentary evidence to provide comprehensive understanding of why what is feared amounts to persecution and why state protection is lacking.

Provides a lot of detail and extensive reference to documentary evidence.

Details his credibility issues well and explains why he is not prepared to accept the claimant's explanations. Good analysis.

In contrast, the 8 reasons that scored a “1” suffered from overuse of boiler plate statements and minimal treatment of key issues. In other cases, an apparent misapprehension of the oral evidence was used to make findings of fact—the claimant testified as being lesbian but the member stated bisexual, or the claimant could not have destroyed her propaganda material since she did not have access to them, but the claimant’s testimony was that she did not have access to them because she destroyed them.

-

References. Referencing applicable legislation, case law or an

IRB policy instrument, such as Chairperson’s Guidelines, informs the parties of the legal and policy authorities used by the member in reaching the decision. In 84% (n=51) of the applicable cases, the study found that members appropriately cited the legislation, case law or Guidelines to support their analysis of the evidence and the conclusions reached. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act was the most cited, followed by Guidelines dealing with gender-based claims, vulnerable persons and child refugee claimants.

Opportunities

-

Chairperson’s Guidelines. The study found that 24 of the 119 claims were gender-based. However, in only 13 of the 24 decisions did the members state either that they were applying Guideline 4 on women refugee claimantsFootnote 4 or the reasons for not applying it. In 10 other cases, the member did not refer to Guideline 4 even though the evidence adduced and the member’s notes in the

HDR identify the claim as gender-related. Instances of possible misapprehension of the Chairperson’s Guidelines, in the opinion of the evaluators, were also found:

- In one case, despite the claimant being male, the member applied the gender Guidelines, as they refer to claims grounded in familial affiliation, kinship. The claim more properly could have been based on simple membership in a particular social group, family.

- Similarly, in another case the member found a well-founded fear by reason of gender violence in relation to the female principal claimant and also the husband. Instead, the member could have considered the husband’s fear as based on membership in a particular social group, the family.

- Finally, one member referred simply to the “Guidelines” in a sexual orientation claim, when no applicable Chairperson’s Guideline existed at the time or in possible reference to UNHCR guidelines on sexual orientation.Footnote 5

Recommendation

A communiqué to members could be helpful in refreshing members’ understanding of how and when Guideline 4 should be applied and, when not applied, to provide a reasoned justification for not doing so.

-

References. Reference to American case law was made in a single claim when the member noted that the claimant only claimed refugee status "defensively" after the claimant was arrested for working illegally, and referred to this as "what the Americans call as a defensive claim". Citing foreign law in an

RPD proceeding should be reconsidered to avoid confusion as to how the claim was treated under Canadian law.

2.4.2 Reasons are transparent and intelligible

What was measured

| | Average score out of 3 (target 2.0) | Percentage of cases scoring at least 2.0 |

|---|

| #29 The member uses plain language | 2.9 | 96% |

| #30 The member gives appropriately clear and concise reasons | 2.2 | 93% |

| #31 Reasons are easily understood and logically sequenced. | 2.2 | 96% |

| Target: 100% of cases achieving at least 2.0 out of 3. |

What the numbers say:

- All scores met the target or fell within the margin of error and are consistent in all three regions and case types

Strengths

-

Transparent and intelligible reasons. Members as a whole excelled in delivering reasons that were clear, concise, in plain language, and logically sequenced in 93% (n=111) of the reasons. Highest scores were found consistently among Western and Central Region reasons, although the small sample size is not conclusive of any one region.

-

Consistency. Members nationally were consistent in delivering quality reasons, scoring over 2.0 out of 3 in several key sub-categories. No statistical difference was found in the level of transparency and intelligibility between: oral and written decisions, accepted and rejected claims, interventions versus non-interventions, and represented versus unrepresented claimants.

-

Clear reasons. As in years past, the study found minor errors in the reasons relating to grammar, typos and spelling. While such errors can be expected, they can confuse the reader and hinder the division’s objective of producing clear and understandable reasons. A final edit should be expected to catch all substantive errors. In one set of written reasons, the wrong country of reference was cited three times, while in another the date of a letter entered into evidence was correctly quoted once and incorrectly elsewhere in the reasons.

2.4.3 Decisions are timely

Why measure this:

A timely decision contributes to resolving uncertainties among the parties and to meeting the

IRB’s mission.

What was measured:

To measure timeliness, the study looked at the entire population of 596 cases finalized in June 2016 and measured the oral reasons rate for allowed and rejected decisions and the median time to finalize a claim.

What the numbers say:

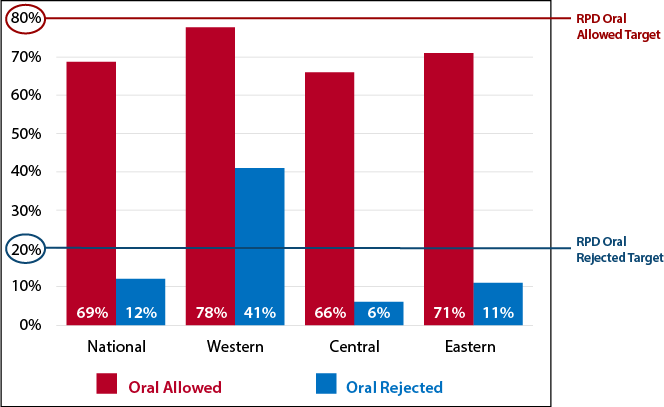

[Alternate format]

What the numbers say

| | Oral Allowed (target 80%) | Oral Rejected (target 20%) |

|---|

| National | 69% | 12% |

| Western | 78% | 41% |

| Central | 66% | 6% |

| Eastern | 71% | 11% |

- Among all claims and applications finalized in June 2016, including the sampling, members delivered oral decisions for allowed and rejected claims 50% of the time.

- A breakdown of the data shows that allowed decisions were delivered orally 69% of the time, shy of the 80% target and slightly lower than the 74% in the 2014-15 study.

- The

RPD rendered rejected decisions orally 12% of the time, a drop from 18% in the last study. Only the Western Region exceeded the 20% target for oral negative decisions.

- As the above charts show, the Western Region is the most successful in reaching oral reasons targets while the Central Region, as the dominant region by volume, effectively pulls the national rate downward; conversely, however, the Central Region has the potential to spring the national rate upward through any efforts of its own to increase its oral reasons rate.

- Of all finalizations during this period, 56% were finalized within 4 months of referral.

3.0 Summary

The members and Registry combined to achieve an aggregate score of 2.2 out of 3. A summary of the main areas of success follows:

- Dockets were organized, complete and timely 75% of the time.

- Members were prepared for their hearing 90% the time.

- Members were always courteous and respectful in over 90% of the hearings.

- An issue agenda was used in 80% of hearings, but may require only a relatively small investment of member time and effort to reach 100%.

- Vulnerable persons were recognized and afforded procedural accommodation.

- Members’ questioning was relevant and organized nearly 90% of the time.

- In 90% of cases, reasons met expectations; key issues were addressed, findings of fact were clear, and analyses explained the member’s decision path.

- Hearings were 45 minutes shorter than those in the previous study.

Opportunities to focus attention are:

- Post-hearing case management depends on accurate and complete information on the Hearing Disposition Record.

- In a few cases, members showed impatience, annoyance, and sarcasm.

- In a fraction of cases, claimants may not have had an opportunity to review and respond to

RPD and Minister’s documents.

- In 12 cases, the members did not explicitly state the determinative issues until the reasons for decision.

- There was uneven application or citation of the Gender Guidelines in nearly half of gender-based claims.

- Minor and substantive errors were found in the reasons.

- 50% of decisions were delivered orally, about 70% allowed and 12% rejected.

Appendix - Checklist

A Timely and complete pre-proceeding readiness

- The file was provided to the member no later than 8 days prior to the proceeding. If there was a delay, specify the number of days prior that the file was provided.

- The file contains all required information and documents. If required information or documents were missing, please specify.

- The file was organized in a logical and standardized manner as established by the division. If applicable, specify how the file was not organized.

- The recording and file indicate that the member was ready for the proceeding.

B Respectful proceedings

- The member treats participants with sensitivity and respect.

- The member ensures parties have an opportunity to present and respond to evidence and to make representations.

- The member identifies when the evidence has not adequately addressed an important issue as identified by the member and asks questions of clarification.

- Communications in the absence of a party is disclosed and summarized on the record.

- Problems with interpretation are identified and addressed.

C Focused proceedings

- The member sets the issue agenda or confirms consent of the parties to the agenda at the start of the proceeding.

- The member ensures the parties focus testimony and documentation on the issues that the member has identified as the relevant issues.

- Did the hearing complete in the time allotted?

- The member's questioning is relevant in relation to the issues identified in the hearing agenda or issues identified in the course of the hearing.

- The member's questioning is focused and organized.

- The member manages challenging situations as they arise.

- During the course of the hearing, the member narrowed the issues.

- The member narrows the issues for final representations.

- The member accommodates needs of vulnerable participants, including unaccompanied minors, to facilitate their presentation of evidence.

- Member deals with oral applications made by parties.

- Member identifies applicable legislation, regulations, Rules or Guidelines.

D Reasons state conclusions on all determinative issues

- Issues identified as determinative at the hearing are dealt with in the reasons.

- Conclusions are based on the issues and evidence adduced during the proceedings.

E Decisions provide findings and analysis necessary to justify conclusions

- The member makes clear, unambiguous findings of fact.

- The member supports findings of fact with clear examples of evidence shown to be probative of these findings.

- The member bases findings on evidence established as credible and trustworthy.

- The member addresses parties’ evidence that runs contrary to the member’s decision, and why certain evidence was preferred.

- The member identifies legislation, rules, regulations, Jurisprudential Guides, Chairperson’s Guidelines or persuasive decisions where appropriate.

- The member takes into account social and cultural contextual factors in assessing witnesses’ testimony.

F Reasons are transparent and intelligible

- The member uses plain language.

- The member gives appropriately clear and concise reasons.

- Reasons are easily understood and logically sequenced.